|

|

Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, Russian Academy of Sciences

Oksana Zvidennaya

|

The Taz. General Information: Endonyms, Ethnographic Groups, Population, and Settlement

The Taz (their endonym is the

Ta-dzy

) is one of Russia’s smallest peoples. Ethnographers categorize them as part of the Amur Sakhalin historical and cultural area, specifically, its Primorye district.

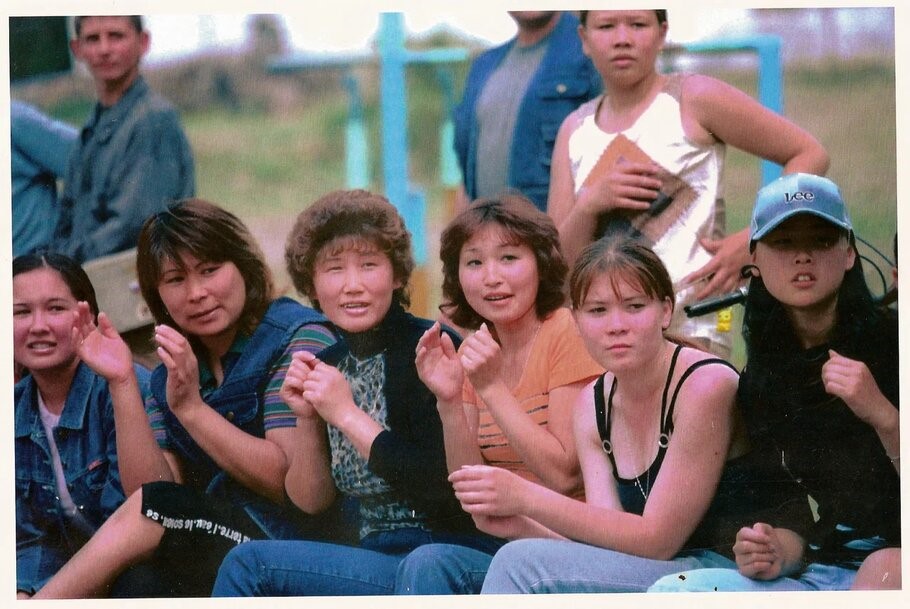

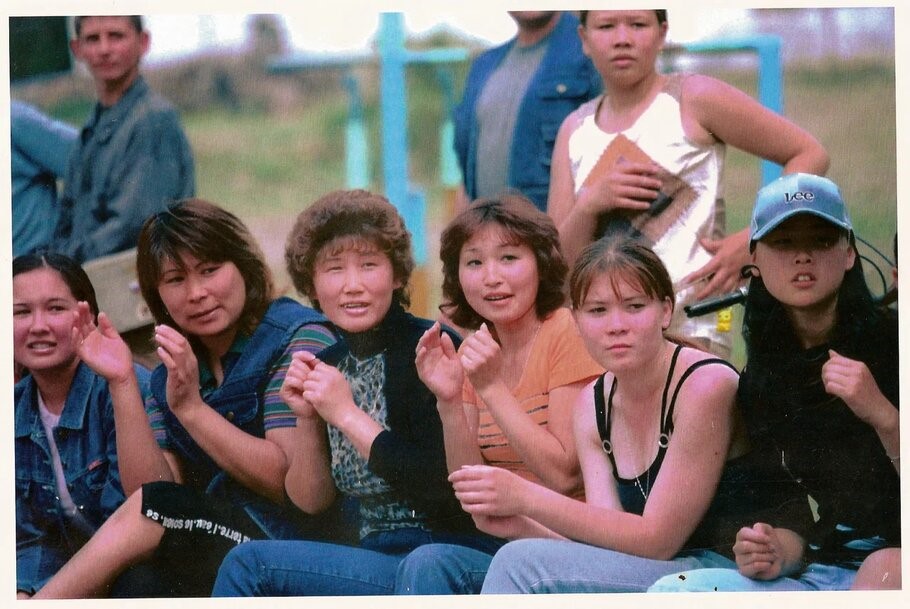

The total number of Taz, according to the 2020 All-Russian Population Census, was 236 people, which is 38 people less than in 2010. The main area of settlement is the Primorsky Territory, outside of which only 15 people live. The basins are evenly distributed between urban and rural areas.

The

Taz

endonym is a phonetic variant of the Chinese

tadzy

/

dadza

/

tadza

(meaning “outlanders”). In the late 19

th

-early 20th century, Sergey N. Bravilovsky and Vladimir K. Arsenyev introduced it into the scholarship. Since then, the South Ussuri

Tadzy

began calling themselves the Taz instead of the

Tadza

or the

Taza

.

Unlike the Ugede, the Nanai, and the Oroch, the Taz are mostly farmers. Hunting, fishing, and gathering used to be important in the past.

The Taz language is a dialect of Northern Chinese. However, it developed on its own and preserved its uniqueness due to the influence of the local indigenous Nanai and Udege languages. The long-standing isolation of most of its speakers also contributed to its preservation. Today, the language has almost entirely lost its communicative functions, for most Taz list Russian as their native language (262 out of 274 respondents as per the 2010 census).

The total number of Taz, according to the 2020 All-Russian Population Census, was 236 people, which is 38 people less than in 2010. The main area of settlement is the Primorsky Territory, outside of which only 15 people live. The basins are evenly distributed between urban and rural areas.

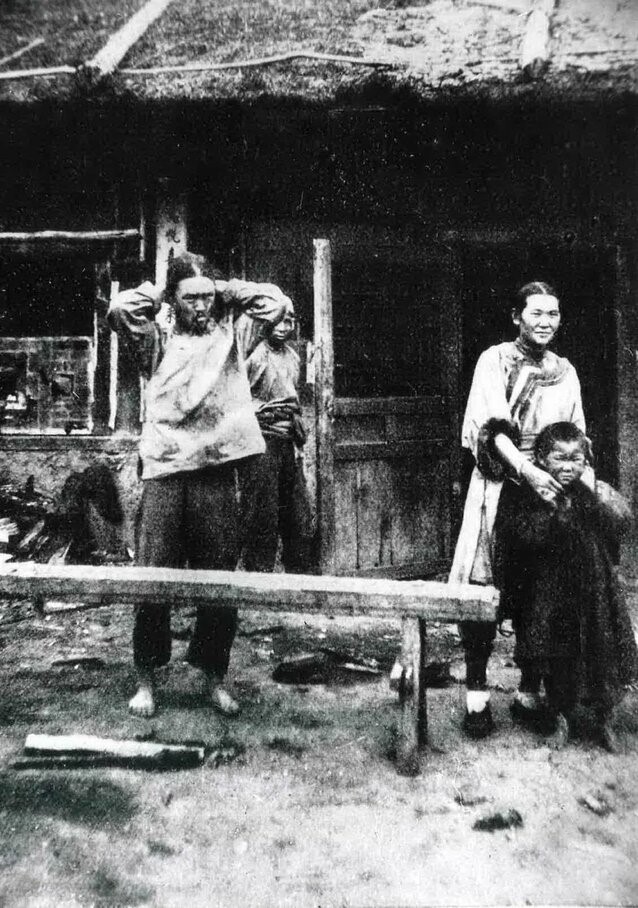

The Taz’s ethnogenesis manifests traces of several ancient strata typical for the ethnogenesis of Tungus Manchu peoples (the Udege, the Nanai, the Oroch) and some other peoples of the Amur Sakhalin region, as well as the later Chinese and Russian strata. The ethnic distinction likely stems from the fact that female natives often married Chinese men who arrived in the area in large numbers in the 19

th

century. The process intensified after the integration of the Ussuri territory.

For a long time, the question of the Taz being a separate people in Primorye and the Amur area had remained. The ambiguous status of the group negatively affected the reliability of available statistics on the numbers and settlement of the Taz. In the mid-19

th

and early 20

th

centuries, the first researchers did not have a consensus on what different groups speaking Chinese should have been called. As a result, each scholar called them differently; some called them Udege, some called them Chinese, Oroch or Oroquen, while others traced their origins to ancient peoples. Most frequently, the Taz were “confused” with the Udege who had not been distinguished from the Oroch at the time because of their anthropological and cultural similarity. Vladimir Arsenyev, the Ussuri territory explorer, was the first to articulate the Taz’s differences from the Udege. He also outlined the degree of Chinese influence over and assimilation of natives from various areas.

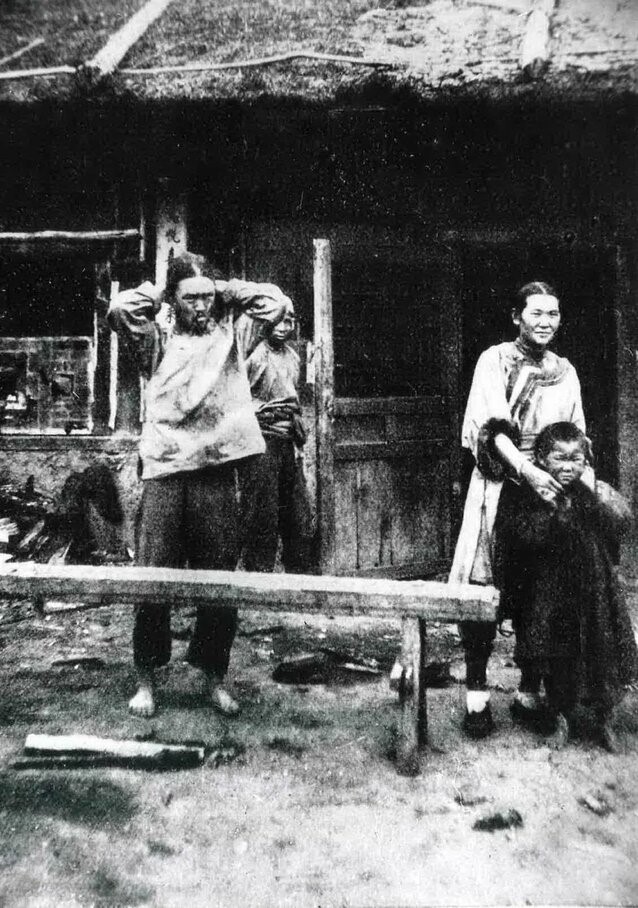

In different historic periods, Taz settlement borders were fluid. Before the Ussuri territory became a part of Russia, its inhabitants lived in homestead settlements along the rivers and bays with plenty of access to food such as animals, fish, and places suitable for farming. In the second half of the 19

th

century, those were mostly lands along the shores of the Sea of Japan from the Amgu river (the north of Primorye) to the border with Korea, and deep inland along the entire right coast of the Ussuri river (and along its major tributaries: the Bikin, the Iman [today’s Bolshaya Ussurka], the Daubikhe [today’s Arsenievka], etc.)

The Taz settlement areas changed as Russia introduced a new land policy in its newly integrated territories. Before the 20

th

century, the Taz were not counted among people eligible to receive land plots. When the area was being actively settled, the Taz lost out the competition for the best land plots to the new settlers. The Taz’s undetermined “indigenous” status regularly made them dependent on the migration policy toward the Chinese that lived in those lands. Local officials were not well-versed in ethnic differences, and they forced out the Taz along with the Chinese thereby forcing the former to migrate increasingly further northeast.

Chinese sources indirectly confirm that the Taz’s ancestors lived in the areas around the Amur and in Primorye as far back as fifteen hundred years ago. Linguistic analysis of the Taz language showed that it has many words that are uncharacteristic for the natives of the Amur region and Primorye and for the Chinese. Scholars of the Far East Yury and Lidia Sem produced a description of the Taz’s ethnic history and culture thereby making a major contribution to the studies of the people. Their research was based on many years of fieldwork in the 1950s-1970s, as well as over 30 yearsof archival research. It later became the first fundamental monograph on the small people from the south of the Primorye area. Explorers, historians, and ethnographers of the 19

th

and 20

th

centuries, such as Leopold I. Shrenk, Nikolay M. Przhevalsky, Ivan A. Lopatin, Lev Ya. Shternberg, Sergey V. Maksimov, Palladius I. Kafarov, B. I. Alyabiev, Vasily P. Margaritov, Nikolay A. Palchevsky, Olimpiada Vasilieva, and others wrote about the Taz as well. Sergey Brailovsky, Vladimir Arsenyev, Victor G. Larkin, Anatoly F. Startsev, Vladimir V. Podmaskin, Anna V. Smolyak, Sergey V. Bereznitsky, and Lidia E. Fetisova were also among them.