|

|

Olga Kazakevich

Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences

|

Northern Selkup Language

I. Sociolinguistic Data

Language Name

Until recently, the principal name was the Selkup language. It was introduced into scholarship in the 1930s. It was based on the endonym of the Northern Selkup group. Since the time of Matthias Castrén (mid-19th century) and until the late 1930s, the name used was the Ostyak-Samoyed language. The linguistic endonym in the Northern group was shyol kumyn ety (literally “the word of forest people”).

Since the time of Georgy N. Prokofiev, the endonym shyol kup was believed to mean “a forest person.” This interpretation became commonplace both in scholarship and among Northern Selkups themselves. However, archival data analysis led to several new noteworthy interpretations. Jarmo Alatalo in 2004 and Evgeny Helimski in 2005 supposed that endonyms of both Northern Selkups and other Selkup groups come from the common Selkup *sʲø “lord” plus derivational *-sǝ suffix meaning “member of family or group,” i.e. “a person from among the lord’s people or family.” In 2019, Anna Urmanchieva proposed another version, namely considering Selkups’ endonym as an old borrowing from the Northern Mansi tongue, which has a similar word combination meaning “a local person” (cf. Northern Mansi sossɑ xum).

Until recently, scholars treated Selkup as a single tongue. A few years ago, they proposed distinguishing two tongues: Northern Selkup and Southern (Central Southern) Selkup. While Northern Selkup can easily be treated as a separate language with its dialects, there are many doubts concerning the unity of Southern Selkup. Today, Southern Selkup is on the brink of extinction, and many of its dialects and entire dialect groups have no native speakers.

General Characteristics

Northern Selkups live over the vast space in the catchment areas of the Middle and Upper Taz and the Middle Yenisei, mostly along the Turukhan, its left tributary, in the Yamal-Nenets autonomous area and the Krasnoyarsk territory. They are a majority in the villages of Ratta, Kikkiakki, Tolka, and Purovskaya in the Yamal-Nenets autonomous area. About 100 Selkups live in Salekhard, the administrative center of the Yamal-Nenets autonomous area. In the Turukhan district of the Krasnoyarsk territory, Selkups live along the middle reaches of the Yenisei, mostly along its left tributary the Turukhan (with its tributaries the Upper and Lower Baikha). Selkups are a majority in the village of Farkovo. They live among Kets in the villages along the Yenisei. Some Selkups live in the village of Kellog on the Eloguy, the Yenisei’s left tributary.

Number of Native Speakers and the Corresponding Ethnic Group

Number of speakers: 879 persons. Source: persons who indicated command of language in the 2010 Census. The number of speakers in traditional Selkup settlements in the 2010 Census: 866 persons. Source: 2010 Census. Number of the ethnic group (per the 2010 Census): 2,346 persons.

No more than 250 persons today are fluent in Northern Selkup.

Age of Speakers

Poorer command among the young generations.

Children who speak the language are very rare.

General characteristics.

All Selkups who speak Selkup also speak Russian. Some members of the older generations (over 60) speak one or more languages of their neighbors: Evenk, Ket, Khanty, Forest Nenets, or Tundra Nenets. Traditionally, Selkup is used in family communication, hunting and fishing, transportation reindeer herding, and folklore. At some point, Selkup was actively used in religious practices (Selkups are animists, and to communicate with other worlds and the spirits of the world around them, they turned to shamans who had helping spirits and could control them), but persecutions of shamans in the 1930s-1940s did leave their mark: today, Selkups do not have any practicing shamans, although the shamanic tradition itself is alive. In the 1930s, Selkup began to be used in new fields: book publication and education, and by the late 20

th

century, it had also come to be used on the radio and TV, and the internet in the early 21

st

century.

Currently, Northern Selkup is taught as a school subject at three village schools and the boarding school in the city of Tarko-Sale. Most Selkup children come to school today without command of their native tongue. School is the only place where they can learn to speak the language of their ancestors, but upon graduation, they do not join the ranks of native Northern Selkup speakers.

Northern Selkup is taught as a subject at the Salekhard Multidisciplinary Vocational College and the Institute of the People of the North at Herzen Russian State Pedagogical University. Currently, the college does not teach the language since there is no instructor.

Out of the five Selkup dialects (sub-dialects), only two (the Upper Taz and the Upper Tolka dialects) still retain some degree of natural transmission from parents to children, while this transmission is interrupted in the other two, and the Eloguy dialect has only one living speaker. All Selkups without exception speak Russian, and those who also speak their mother tongue are bilingual. Russian dominates in virtually all Northern Selkup settlements in all communication fields, including family. Even with living intra-family language transmission, its field of use is steadily shrinking in every subsequent generation.

Vitality Status

2B for the Upper Taz (Krasnoselkupskaya Tolka, Ratta, Kikkiakki) and the Upper Tolka (the villages of Tolka Purovskaya, Bystrinka trading post) dialects. Some families, particularly those living in camping areas, pass the language to their children.

2A for the Middle Taz (Krasnoselkup, Sidorovsk, Sovetskaya Rechka) and Turukhan (Farkovo) dialects and for native speakers of the Upper Tolka dialect in Tarko-Sale.

1B for the Eloguy dialect (Kellog) and speakers of the Turukhan dialect in Turukhansk.

Use in Various Fields

|

Field

|

Significance

|

Comments

|

|

Family and everyday communication

|

Yes

|

|

|

Education: kindergartens

|

Yes

|

Taught as a subject.

|

|

Education: school

|

Yes

|

Taught as a subject.

|

|

Higher education

|

Yes

|

Taught as a subject.

|

|

Education: language courses/clubs

|

|

|

|

Media: press (including online publications)

|

Yes

|

The Northern Territory

(Krasnoselkup) district newspaper periodically publishes a Selkup page (1-2 times a year).

|

|

Media: radio

|

Yes

|

Until recently, Salekhard did radio broadcasts in Northern Selkup twice a week. Today, broadcasts are mostly moving on the internet.

|

|

Media: TV

|

Yes

|

|

|

Culture, (including existing folklore)

|

Yes

|

|

|

Literature in the language

|

no

|

|

|

Religion (use in religious practices)

|

Yes

|

Traditional rituals of feeding the fire, bringing gifts to the spirits of forest, river, etc.

|

|

Legislation + Administrative activities + Courts

|

Yes

|

The laws of the indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North and the Constitution of the Yamal Nenets autonomous area are translated into Northern Selkup. Although virtually no one uses these translations.

|

|

Agriculture (including hunting, gathering, reindeer herding, etc.)

|

Yes

|

Periodically used in reindeer herding and in hunting.

|

|

Internet (communication/sites in the language, non-media)

|

Yes

|

To a small degree.

|

Information on the Writing System

In the early 1930s, a Latin-based alphabet mostly based on the Middle Taz dialect was developed for Northern Selkup as part of the project for designing alphabets for the peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Russian Far East; textbooks were published, and Selkup children were taught at school in their native tongue. In 1937, Selkup writing was rapidly switched to the Cyrillic alphabet, which destabilized both the Selkup writing and school education in Northern Selkup. Gradually, it was transformed from a language of instruction into a school subject, and in the mid-1950s, it was removed from the school curriculum. At the same time, textbooks were no longer published in Selkup. As for fiction, it has never been published in Northern Selkup except of two songs’ lyrics published in the Severnye Rossypi (Northern Scatterings) collection in 1962. Since the early 1980s, a new attempt to make Selkup a written tongue was made. The new Cyrillic-based alphabet based primarily on the Northern idiom was somewhat modified over the last two decades to better render the phonemes of the base dialect.

At the moment, Selkup school textbooks were published for grades 1-9, as well as a reader for grade 2, a student’s Selkup-Russian and Russian-Selkup dictionary, a Picture Dictionary, and Grammar Tables. School textbooks were authored by teachers of Northern Selkup. Additionally, a Selkup textbook for universities was published. It was the first university-level textbook of the language of an indigenous small-numbered people of the North. In addition to textbooks and academic folklore publications, a small book of Selkup songs’ texts was published in the late 1990s..

It should be noted that Northern Selkup writing is primarily used in education. The Northern Selkup writing (both in the Northern dialect and Southern dialects) is virtually unused beyond schools and universities.

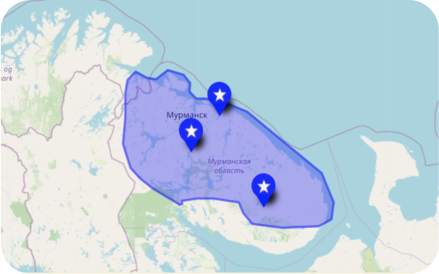

Geographical Characteristics

Constituent Entities of the Russian Federation with Ethnic Communities

.

The Yamal Nenets autonomous area, the Krasnoyarsk territory, the Tyumen region (city of Tyumen)

Total Number of Traditional Native Settlements

12

Historical Dynamics

In the early 20

th

century, all Northern Selkups spoke their ethnic tongue. Command of Russian was not universal at the time. However, quite a few Selkups, along with their mother tongue, knew the languages of the neighboring peoples: Ket, Evenk, Khanty, and Nenets. Intensive contact with Russians since the mid-1920s and the spread of school education advanced better command of Russian. By the early 1950s, the knowledge of Russian had become quite common. At the time, the native tongue still held its position in the north largely because many villages had a Northern Selkup majority. By the late 1970s, as the demographic situation changed, so did the linguistic situation. Particularly sharp shifts occurred over the last 35-40 years.

Numbers of native speakers and the corresponding ethnic group per different Censuses (starting in 1897) and per other sources.

|

Census yearГод переписи

|

Numbers of speakers, persons

|

Numbers

of

ethnic

group,

persons

|

Notes

|

|

1897

|

|

5,805

|

All Selkups (Ostyak Samoyeds) without division into Northern and Southern

|

|

1926

|

1,583

|

1,630

|

Mostly Northern Selkup speakers.

|

|

1939

|

—

|

2,604

|

No information on the language

|

|

1959

|

1,923

|

3,704

|

All Selkups (Ostyak Samoyeds) without division into Northern and Tomsk Selkups

|

|

1970

|

2,188

|

4,282

|

All Selkups (Ostyak Samoyeds) without division into Northern and Tomsk Selkups

|

|

1979

|

2,145

|

3,565

|

All Selkups (Ostyak Samoyeds) without division into Northern and Tomsk Selkups

|

|

1989

|

1,477

|

1,999

|

|

|

2002

|

1,199

|

2,269

|

|

|

2010

|

879

|

2,346

|

|

|

2020

|

973 Northern Selkup

|

3,491

|

All Selkups (Ostyak Samoyeds) without division into Northern and Tomsk Selkups

|

II. Linguistic Data

Position in the Genealogy of World Languages

Uralic languages > Samoyedic branch > Selkup group.

Dialects

Northern Selkup exists as an aggregation of local variants, dialects, or subdialects functioning in several villages in the Krasnoselkup and Pur districts of the Yamalo-Nenets autonomous area and the Turukhan district of the Krasnoyarsk territory. As of today, five dialects have been preserved to various degrees: Middle Taz (villages of Krasnoselkup, Sidorovsk, individual dialect speakers also live in the village of Severnaya Rechka of the Turukhan district), Upper Taz (Tolka of the Krasnoselkup district, Kikkiakki, Ratta, individual dialect speakers also live in Krasnoselkup, the district center); Upper Tolka (Lariyak) (village of Tolka, Bystrinka trading post of the Pur district, city of Tarko-Sale), Turukhansk (villages of Farkovo, Turukhansk, individual dialect speakers also live in Sovetskaya Rechka village in the Turukhansk district), Eloguy (village of Kellog of the Turukhansk district). All dialects are mutually understandable, although speakers are aware of the differences between their variants and their neighbors’ variants, and, as a rule, they view the neighbors’ variants as “less correct.”

Brief History of Academic Research of the Language

Northern Selkup dialects have been unequally doсumented. The most extensively documented Middle Taz dialect served as the basis for developing the alphabet in the 1920s-1930s. This dialect’s materials are contained in Matthias Castrén’s records. This dialect was described in the grammar books by Georgy N. Prokofiev (1935, based on his experience of working as the principal at the boarding school in Yanov Stan) and Ariadna I. Kuznetsova, Evgeny A. Helimski, and Е.V. Grushkina (Kuznetsova et al. 1980) and in the textbook for universities and teacher vocational colleges (Kuznetsova et al. 2002); there are also some grammar sketches of this dialect by Georgy N. Prokofiev (1934; 1937), Ekaterina D. Prokofieva (1956), Evgeny A. Helimski (1993; 1998), and Olga A. Kazakevich (2010; 2022). The vocabulary of the Middle Taz dialect is presented in István Erdélyi’s first Selkup dictionary (Erdélyi 1969) compiled from grammatical descriptions of Georgy N. Prokofiev and Selkup textbooks of the 1930s; see also the Selkup-Russian Dictionary in (Kuznetsova et al. 1993) and the Russian-Selkup Dictionary and some other kinds of Selkup dictionaries in (Kazakevich et al. 2002). The Selkup-Russian and Russian-Selkup Student Dictionary by Sergey I. Irikov is based on materials from the Middle Taz dialect. The dictionary compiled by Fyodor G. Maltsev in 1903 and published by Evgeny A. Helimski and Karhs (2001) reflects the lexis of a subdialect of the Turukhansk dialect. Finally, the Northern Selkup dialect dictionary (Kazakevich, Budyanskaya 2010) includes the lexis of all Northern Selkup dialects.

Typological and Area Linguistic Traits

Two ways of marking an object. A given sentence’s information structure plays a determining role in selecting the way of marking an object.

Two types of verb conjugation: verb object conjugation and verb-subject conjugation. A given sentence’s information structure plays a determining role in selecting the conjugation type for transitive verbs.

Three numbers: singular, dual, and plural.

Spatial deixis has three meanings: close to the speaker, far removed from the speaker, and close to the listener.

Morphology

Northern Selkup has the following parts of speech: nouns, adjectives, pronouns, numerals, verbs, adverbs, particles, postpositions, preverbs, conjunctions, and interjections.

The noun has the following categories: number (singular, dual, plural), case (Nominative, Accusative, Genitive, Instrumental, Abessive, Translative, Comparative, Dative (Allative), Inessive, Locative, Ablative, Prosecutive, Vocative), declension type (non-possessive, possessive conveying the possessor’s person and number). Nouns can have conjugatable verbal forms.

The noun in Selkup has singular, dual, and plural forms.

Singular does not have specific markers. Dual is used for homogeneous non-paired items. Nouns meaning paired items do not have dual forms.

Kazakevich O.A., Budyanskaya E.M. Dictionary of the Selkup Language’s Dialects (the Northern Idiom) // Kazakevich O.A., ed. Ekaterinburg: Basko, 2010.

Kazakevich О.А. “The Selkup Language (the Northern Idiom, the Middle Taz Subdialect)” // Kazakevich O.A., Budyanskaya E.M. Dictionary of the Selkup Language’s Dialects (the Northern Idiom). Ekaterinburg: Basko, 2010. P. 270-352.

Kazakevich О.А., Kuznetsova А.И., Helimski Е.А. The Selkup Language Sketches. The Taz Dialect. Vol. 3. Moscow, 2002.

Kuznetsova A.I. Kazakevich O.A., Ioffe L.Yu., Helimski E.A. “The Selkup Language Sketches. The Taz Dialect.” // Kuznetsova A.I., ed. Vol. 2. Texts. Dictionary. Moscow. 1993.

Prokofiev G.N. “The Selkup (Ostyak-Samoyed Language)” // Language and Writing of the Peoples of the North. Part 1. Languages and Writing of the Samoyed and Finno-Ugric Peoples. Moscow, Leningrad, 1937. P. 91-123.

Prokofiev G.N. The Selkup (Ostyak-Samoyed) Language. Leningrad: Institute of Peoples of the North at the CEC of the USSR Press, 1935.

Prokofieva E.D. “The Selkup Language” // Languages of the Peoples of the USSR. Vol. 3 Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic Languages. Moscow: Nauka, 1966.

Helimski Eugene. “Selkup” // Daniel Abondalo (ed.). The Uralic languages. London; New York: Routlege, 1998. P. 548-579.

Helimski E., Kahrs U. Nordselkupisches Wörterbuch von F.G.Mal’cev (1903) / (Hamburger sibirische und finnisch-ugrische Materialien. Band 1.) Hamburg, 2001.

Erdélyi I. Selkupisches Wörterverzeichnis. Tas Dialekt. Budapest, 1969.