Uilta Language

I. Sociolinguistic Data

I.1. Language Names

Until recently, Orok was the most common name of the language. The alternative designation, although more often used over the last two decades, does not yet have a definitive variant in Russian: in addition to the officially approved Uilta, there are also such versions as язык уильта, язык ульта, уильтинский язык, уйльтинский язык (language of Uilta, language of Ulta, Uilta language, Ulta language). The name variants are related to the different names of the ethnic group: Orok or Uilta (Ulta). In this article, we will favor Uilta and Uilta language. These are the names used, for instance, in Букварь (ABC) in Uilta and Тунгусо-маньчжурские народы Сибири и Дальнего Востока (The Manchu-Tungus peoples of Siberia and the Far East), both published in 2022.

As for the use of Orok as self-designation, T. Petrova gave the following explanation in 1967: “Oroks call themselves Oroks only when communicating with the ethnic groups that already use this name”. It should be noted that the name Orok was used not only by Russians but also by other ethnic groups that live or used to live next to Uilta. For instance, the Uilta people were known as orokko (orohko) among Ainu. Ch. Taksami wrote that Nivkhs used the word орӈрку (that has the same origin) to “define a wide circle of Tungus people – Ulchi, Oroks, Orochs, etc.” In Uilta, this word sounds like orokko. Most likely, it stems from the following forms: *oroŋkān (sing.) ~ *oroŋkār (pl.). The suffix of *-ŋkān (sing.) ~ *-ŋkār (pl.) indicates an inhabitant of a specific area. Whereas the root *oro- means ‘location, place of residence’, i.e. *oroŋkān — is an ‘inhabitant of this settlement, a local, a native resident of this area’. At the same time, the phonetic appearance of orokko shows that for Ulita it was not an indigenous but a borrowed word (from some language of the Northern branch of the Manchu-Tungus family that had probably never reached us). If it was an indigenous word that had evolved by the rules of historical changes typical for Uilta, it would have ended up as *оротто. The borrowed nature of ethnonyms is the fact that is well-known to linguists. It often happens that the name of an ethnic group appears first within a neighboring group (it describes the ethnos from outside as a single group with specific linguistic and cultural features) and not within the ethnos itself (where it is often more important to maintain an internal division into clans, local groups, instead of ensuring ethnic consolidation). As we will see later, the second ethnonym of Uilta is also of an external origin.

The ethnonym that they use as self-designation is currently formalized in Russian as уйльта. It corresponds to the indigenous words that various researchers recorded as уилта, уjлта, ул’та. It also has cognate words in Ulchi (улча [Uilta, Orok]) and the Lower Negidal (олчан [Udege]). Out of the three indicated forms of Uilta — уилта, уjлта, ул’та, — the earliest, admittedly, was ул’та. The palatalization (softening) of л [l] in this word indicates that the sound л [l] used to be followed by the sound и [i], i.e. the initial Uilta form was *улитта. Afterwards, this и [i] skipped to the initial syllable (such irregular movements within a word are possible in the world’s languages), which resulted in уилта. Both ул’та (< *улитта) in Uilta and улча [Uilta] in Ulchi stem from the form *улинчан. The word was borrowed from Oroch or Udege (or from their common ancestor), where it looked like*улинка̄н (the historic shift нк > нч was natural for Ulchi and Uilta, moreover, Uilta had a further development of нч > нт > тт). This word *улинка̄н is translated as ‘river dweller’: in Oroch and Udege, the word ули means ‘river’ (in Udege, it also means ‘water’), whereas the suffix *-нка̄н means ‘a resident of this settlement’ (and historically corresponds to the above-mentioned suffix of *-ӈка̄н).

I. 2. General Characteristics

2.1.

The Number of Native Speakers and the Corresponding Ethnic Group

The 2020 Census provided completely improbable data regarding the Uilta language: it indicated that 73 people mastered Uilta. With the total Uilta population amounting to 268 people (based on the same Census), it looked like 27% of representatives of this ethnic group spoke the language, which would have been an exceptionally favorable result for such a small people. However, both researchers and teachers currently working on the creation of relevant teaching materials know perfectly well that there are currently no more than 3-5 people speaking Uilta.

In the first All-Russian Population Census of 1897, there were recorded 743 Uilta (Oroks), including 304 located in the southern part of the island and 445 in the northern part. The 1926 Census recorded 162 Oroks. These data covered only the northern part of Sakhalin; based on the Convention on Fundamental Principles for Relations between Japan and the USSR signed in 1925, the Soviet-Japanese border on Sakhalin ran along the 50th parallel by the Treaty of Portsmouth of 1905. The Japanese statistics indicated that in 1907 the southern part of Sakhalin was inhabited by 334 Orochons. It was reported that after World War II, when the USSR reclaimed Sakhalin from Japan, several Uilta moved from the southern part of Sakhalin to Hokkaido Island. Some Uilta living in the southern part of Sakhalin even now continue to have Japanese names and surnames; as late as the end of the 20th century, some southern Uilta of the older generation still remembered Japanese.

The Censuses of 1959, 1970, and 1979 did not include Oroks as a separate nationality. Based on the 1989 Census, there were 190 Oroks. but it is also important to cite the alternative statistic data collected by the expedition of the Moscow Institute of Ethnography of the RAS, USSR, in the 1990s (the data covered three settlements of compact residence of Uilta):

|

Locality

|

Uilta

|

|

Val

|

144

|

|

Nogliki

|

20

|

|

Poronaysk

|

156

|

Based on the provided data, these three settlements alone had 320 Uilta residents (and not 190 as indicated by the Census carried out only a year before). These numbers seem more consistent with the data provided by the following Censuses: the 2002 Census recorded 346 Uilta, the 2010 Census — 295 Uilta.

I.2.2.

Age of Speakers

Only a handful of elderly people speak Uilta.

I.2.3. Sociolinguistic Characteristics

To date, the transmission of Uilta from parents to children has completely ceased. Furthermore, there are many Uilta families in which the representatives of three generations speak no native language: neither children nor parents or “young” grandparents speak any Uilta. The age of the few people proficient in Uilta is about 80 years old. Under such circumstances, the extinction of the language is virtually irreversible.

I.2.3.2. Use in Various Spheres

The natural functioning of Uilta ceased in all spheres. The language is only rarely used for some artificial occasions: during joint projects between native speakers and researchers, national events, and preparation of school textbooks. At the same time there is only one school in Poronaysk that organizes an optional Uilta course.

|

Sphere

|

Use

|

|

Family and everyday communication

|

No

|

|

Education: nursery school

|

No

|

|

Education: school

|

Yes

|

|

Education: higher education

|

No

|

|

Education: language courses/clubs

|

No

|

|

Media: press (incl. online editions)

|

No

|

|

Media: radio

|

No

|

|

Media: TV

|

No

|

|

Culture (incl. live folklore)

|

No

|

|

Fiction in native language

|

No

|

|

Religion (use in religious practice)

|

No

|

|

Legislation + Administrative activities + Justice system

|

No

|

|

Agriculture (incl. hunting, gathering, reindeer herding, etc.)

|

No

|

|

Internet (communication/ existence of websites in native language, not media)

|

No

|

I.2.4.

Literature

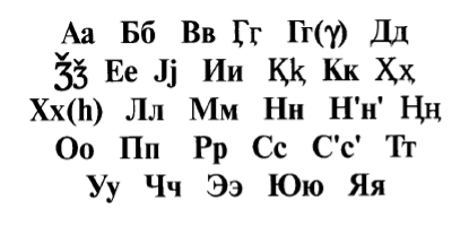

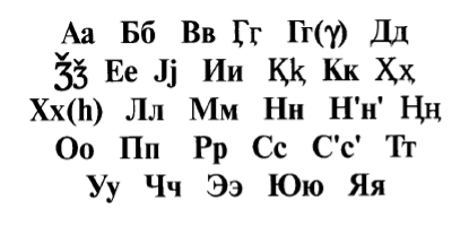

The first edition in Uilta based on its alphabet (instead of transcription) was Орокско-русский и русско-орокский словарь (Orok-Russian and Russian-Orok Dictionary) by L. Ozolinya and I. Fedyayeva published in 2003. It used the following alphabet version:

The first textbook in Uilta was

Уилтадаирису.

Первая книга для детей и взрослых, желающих научиться уилтинскому языку

(The first book for children and adults who wish to learn the Uilta language) published in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk in 2007. This book was compiled by a team of authors led by

Jirô Ikegami,

professor emeritus of the Hokkaido University: E. Bibikova, L. Kitajima, S. Minato, T. Roon, I. Fediayeva.

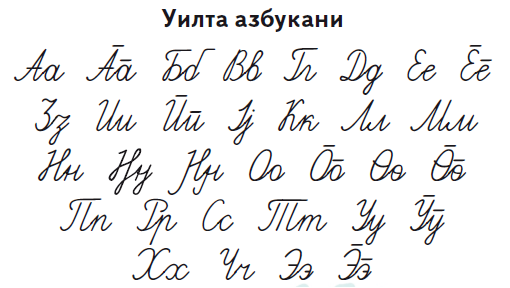

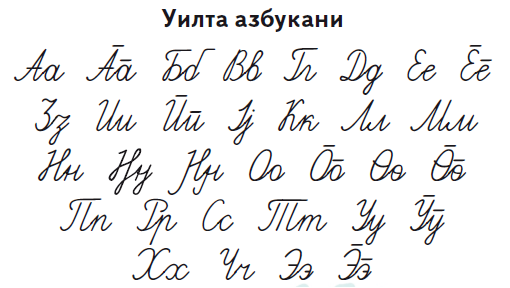

This ABC used a somewhat different version of alphabet:

This version of the alphabet fully corresponds to the phonological system of the Uilta language: there is a separate letter for every phoneme, i.e. every separate sound within the system.

The Букварь (ABC) complied by E. Bibikova, Minato Siruko, L. Missonova, and A. Pevnov used virtually the same version of the alphabet. There is but one purely graphic difference: instead of the symbol ӡ, it uses the symbol ӡ̌. An additional symbol ғ was also introduced into the alphabet. Although the letters г and ғ are used to designate the sounds g and γ – positional variants (g is found at the beginning of words and in consonant clusters, whereas γ – between vowels) – these sounds are relatively far from each other phonetically. During the preparation of this handbook, in accordance with the teaching method for children who have not mastered their mother tongue, it was decided to add a letter that would facilitate the task of reading words for students.

I.3. Geographic Characteristics

I.3.1.

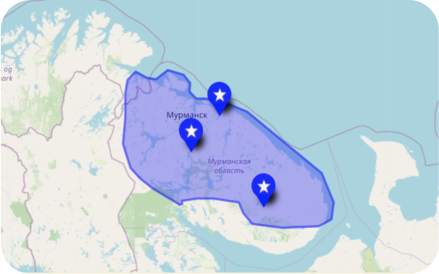

The area of Uilta compact residence is Sakhalin Island: Nogliksky and Districts of Sakhalin Oblast, a small number of Uilta also lives in settlements in Okhinsky and Alexandrovsky Districts.

I.3.2. Total Number of Traditional Native Settlements

In all settlements inhabited by Uilta, they constitute a minority compared to other ethnic groups. Based on the 2010 Census, there are only three settlements with over 10 Uilta inhabitants.

I.3.3.

List of Settlements

Below, you’ll find the list of settlements with over 10 Uilta inhabitants (based on the 2010 Census). The table also contains the total population of the given settlement and the percentage attributed to Uilta.

|

Locality

|

Uilta

|

Total population

|

Uilta percentage of total population

|

|

Val

|

87

|

893

|

9,7%

|

|

Nogliki

|

23

|

10151

|

0,23%

|

|

Poronaysk

|

99

|

16085

|

0,62%

|

I.4. Historical Dynamics

Below, you’ll find the table with the number of native speakers recorded in Censuses and their percentage of total Uilta population. Dark shading in cells indicates lack of data.

|

Census Year

|

1897

|

1926

|

1959

|

1970

|

1979

|

1989

|

2002

|

|

Size of ethnic group

|

743

|

162

|

|

|

|

190

|

346

|

|

Language proficient

|

Not taken into account separately

|

162

|

|

|

|

89

|

64

|

|

% of proficient speakers of the total ethnic group

|

Probably close to 100 %

|

100%

|

|

|

|

47%

|

18,5%

|

The two latest Censuses (2010 and 2020) differentiated two questions: which language the respondent considers his/her native one and whether he/she is proficient in the national language. These are the results concerning Uilta:

|

Census Year

|

2010

|

2020

|

|

Size of ethnic group

|

295

|

268

|

|

Indicated as native language

|

25

|

100

|

|

Language proficient

|

47

|

73

|

|

% of proficient speakers of the total ethnic group (based on the Census data)

|

16%

|

27%

|

For numerous reasons, the data provided by Censuses are virtually uninformative for Uilta: the total population of the ethnic group is completely misrepresented, and in some of the Censuses of the second half of the 20th century, Uilta is not even indicated as a separate nationality. The data about fluent speakers are unreliable as well, thus, in 2020, there were no more than 3-5 people speaking the language, instead of 73 as stated by the Census. It does not necessarily indicate an error in the methodology of calculation. More likely, we are witnessing the phenomenon scholars described as the vagueness of the native language concept found in the 1989 Census. Furthermore, V. Belikov showed in Надежность советских этнодемографических данных (The reliability of the Soviet ethnodemographic data), that even very careful calculations sometimes yielded absurd results: for the peoples of the North, as a rule, “based on census statistics, the further they are from the settlements of ethnic compact residence, the better they master their ethnic language and the less they speak Russian.” In other words, it is the northern townspeople, who live in a Russian-speaking environment, that indicate their knowledge of ethnic language more eagerly than the Northerners living in small settlements in their own linguistic environment. The issue here is that the people far from home in foreign ethnic environments struggle with their ethnic identity, feel the need to prove their belonging to a group (the so-called ethnic identifiers), and they choose their native language as such a proof.” Meanwhile, we provided the statistics that showed Uilta in an absolute minority even in the settlements of their compact residence. It is quite possible that this situation amplifies the symbolic function of the language, and its role as an identity marker. Meanwhile, the respondent may only know some common words and simple phrases.

II. Linguistic Data

II.1.

Position in the Genealogical Classification of World Languages

Uilta, together with Ulchi and Nanai, belongs to the Amur-Sakhalin branch of the Manchu-Tungus language family, and it is particularly close to the Ulchi language.

There are two dialects that can be distinguished within the Uilta language, Northern and Southern, and they correspond to two ethnographic Uilta groups. The Northern dialect was spoken by the Uilta living in the northern part of the Sakhalin Island, currently in Nogliki and Val. In Uilta, this group was called доронне̄ни (Doro is the northern Sakhalin). The Southern dialect was spoken by the Uilta who lived mainly in Poronaysk and the villages of Rechnoye and Ustye by the mid-20th century, and now only in Poronaysk. This group was called сӯнне̄ни (Sun is the southern Sakhalin). The dialects are relatively close, their main differences lie in the phonetic appearance of words (e.g. North. дӯ ~ South. дө̄ [two], North. субгу ~ South. сугбу [fish skin]).

II.3.

Short History of Studying the Language

The first recordings in Uilta (approximately 350 words) were made by Japanese researcher Matsuura Takeshiro (1818–1888) in the mid-19th century. There is a memorial sign in his honor at the mouth of the Pugachevka River, on Sakhalin. A much more extensive material was collected in the early 20th century (circa 1904) by Bronislav Pilsudsky, who was exiled to Sakhalin. He compiled a dictionary, approximately 2.000 words, wrote down some texts, and made grammatical notes. In 1928, considerable lexical material was gathered by Hisaharu Magata, but his dictionary was published much later, in 1981. In the second half of the 20th century, Jirô Ikegami worked with the Uilta who moved to Hokkaido after World War II. He published a considerable number of works on Uilta and a dictionary in Uilta, approximately 4,500 words. Unfortunately, Magata’s dictionary and major works by Ikegami were written in Japanese, and therefore, are little known outside of Japan. The first substantial grammatical description of the Orok language was published by T. Petrova in 1967. In 2001, L. Ozolinya published Орокско-русский словарь (Orok-Russian Dictionary). In 2003, L. Ozolinya and I. Fedyaeva published Орокско-русский и русско-орокский словарь (Orok-Russian and Russian-Orok Dictionary). In 2013, L. Ozolinya published Грамматика орокского языка (Grammar of the Orok Language).

II.4.

Linguistic Data

The system of vowels of the Uilta language comprises seven phonemes, and each one of them has a short and a long variant (the letter of alphabet corresponding to the sound is indicated in brackets):

|

|

Row

|

|

|

Front

|

Central

|

Back

|

|

High

|

i

(

и

)

ī

(

ӣ

)

|

|

u

(

у

)

ū

(

ӯ

)

|

|

Mid

|

e

(

е

)

ē

(

е̄

)

|

ə

(

э

)

ə̄

(

э̄

)

|

o

(

ө

)

ō

(

ө̄

)

|

|

ɔ

(о)

ɔ̄

(о̄)

|

|

Low

|

|

а

(

а

)

ā

(

а̄

)

|

|

Uilta is ruled by vowel harmony. In a language with vowel harmony, all vowels are divided into two sets on a specific basis, and each word may only contain the vowels of the same set. In different languages, the vowel harmony within a word may be based on different characteristics (or features) of vowels. One of the major consequences of vowel harmony is that the suffixes have to have several variants because in order to preserve vowel harmony, a suffix has to “adapt” its vowels to the vowels of the word stem. In other words, a suffix has several (at least two) harmonic variants, and the choice of one of them is determined by the word stem. A more informal definition of the vowel harmony principle is the following: the vowel of the initial syllable imposes the choice of all other vowels within the word.

The previous paragraph describes the ideal system of vocalism based on the vowel harmony principle. Such a system was proper to a very distant ancestor of Uilta, the Proto-Tungusic language. It was the common ancestor of all known Manchu-Tungus languages. Naturally, there are no written monuments of this language, it began to splinter into dialects that gave birth to separate branches of the Manchu-Tungus language family approximately 2.000 years ago. Researchers succeeded in reconstructing certain information about it by comparing the materials of Manchu-Tungus languages. All these languages managed to preserve their vowel harmony in one form or another, thus, the following system could be reconstructed for the Proto-Tungusic language: the vowels of each degree of height (high, mid, low) had two variants, a relatively high (more open) and a relatively low (more closed); the harmonic pair consisted of the vowels a (as a relatively low vowel) and ə (as a relatively high vowel, in orthography э). A word could only contain the vowels of one of two harmonic sets: either relatively high or relatively low. This protolingual system of vowel harmony was preserved virtually intact in the Even language. In its purest form, this system enabled the observer to predict the harmonic set to be used throughout the entire word just by looking at the initial syllable, and the harmonic variant of the suffix in particular).

However, one protolanguage can bring about a whole family of different languages that are often not mutually intelligible, because each of its descendants (and the descendants of the descendants) evolves according to its own laws, it undergoes numerous changes on every level that form its unique identity. These changes can affect the system of sounds as well. In Uilta, for instance, one does not distinguish anymore between two i-like vowels and two u-like vowels (a relatively higher and a relatively lower). This is why the vowels of the initial syllable (that determine the harmonic set of the word) are divided into two groups the following way:

|

1st harmonic set (relatively lower)

|

e

ē

|

а

ā

|

ɔ

ɔ̄

|

i

ī

|

u

ū

|

|

2nd harmonic set (relatively higher)

|

|

ə

ə̄

|

o

ō

|

In other words, all vowels, with the exception of i, ī, u, u, unambiguously determine the harmonic set of the word. It can easily be demonstrated by the way the vowel is selected for the accusative indicator: for the words of the 1st harmonic set, the vowel in the accusative indicator is а, for the 2nd set —

э

:

Words with the vowels of the 1st harmonic set in the initial syllable

|

meaning

|

nominative case

|

accusative case

|

|

widow

|

на̄ву

|

на̄вумб

а

|

|

earmuffs, part of a headwear that covers ears

|

се̄пту

|

се̄птумб

а

|

|

dish made of berries (cranberries, lingonberries) ground with milk and seal fat

|

соли

|

солимб

а

|

Words with the vowels of the 2nd harmonic set in the initial syllable

|

meaning

|

nominative case

|

accusative case

|

|

school of fish

|

пэкту

|

пэктумб

э

|

|

apron

|

өлтөпту

|

өлтөптумб

э

|

Since the Uilta sounds of i, ī represent the convergence of two i-like vowels that initially belonged to two different harmonic sets, and the sounds of u, ū are also the convergence of two u-like vowels from two different harmonic sets, in the modern Uilta, the sounds of i, ī, u, u of the initial syllable do not impose the harmonic set of the word. Among the words with these vowels in their initial syllables, there are those that belong to the 1st harmonic set (since in the protolanguage, they used to have vowels i, ī, u, ū of the 1st harmonic set), and those that belong to the 2nd harmonic set (since in the protolanguage, they used to have vowels i, ī, u, ū of the 2nd harmonic set).

|

meaning

|

nominative case

|

accusative case

|

|

brush

|

пулчи

|

пулчимба

|

|

comb

|

сигӡ̌ипу

|

сигӡ̌ипумба

|

Words with

i, ī, u, ū

of the 2

nd

harmonic set in the initial syllable

|

meaning

|

nominative case

|

accusative case

|

|

steam, vapor

|

сугби

|

сугбимбэ

|

|

drill

|

пӣпу

|

пӣпумбэ

|

Uilta also has an additional rule of vowel harmony: if the vowel of the syllable immediately preceding the suffix is either

о

or

ө

, the suffix will have

о

instead of

а,

and

ө

instead of э:

|

meaning

|

nominative case

|

accusative case

|

|

a tree thrown over a river or a stream that allows to cross the liver

|

тоово

|

тоовомб

о

|

|

scraper for skins

|

төттө

|

төттөмб

ө

|