Eastern Khanty

I. Sociolinguistic data

I.1. Existing alternative names.

Currently, the term

Kantyk language

is also used, which refers specifically to the Eastern Khanty language. There is also an obsolete term

Ostyak,

which refers to the Khanty language as a whole, but with clarifications can also apply to individual Khanty dialects: for example, the obsolete name for the Surgut dialect of Eastern Khanty is “the language of the Surgut Ostyaks”.

I.2. General characteristics

I.2.1. Number of native speakers and the corresponding ethnic group

It is impossible to estimate the number of speakers of Eastern Khanty based on census data. Although ethnographers and linguists are aware of the fundamental differences between the three ethnographic groups (Southern, Northern and Eastern Khanty) and their languages, in all censuses conducted in the Russian Empire, the USSR and Russia, the Khanty have always been counted as a single people with no divisions into individual ethnographic groups.

Thus, the census of 2010 takes into account speakers of both Northern Khanty and Eastern Khanty together (the Southern Khanty language has disappeared by now). In 2010, 30,943 people called themselves Khanty, and approximately 11.5 thousand people indicated Khanty as their native language.

At the same time, when answering the question about the native language, people often thought that “native language” was not the language learned from their mother and used as the main language of communication, but the traditional language of the ethnic group. This means that the Khanty language could have been indicated as native by those who did not speak it. In the census of 2010, in addition to the question about the native language, a question about language proficiency was added and approximately 9.5 thousand Khanty responded as “proficient”.

According to the experts from the project “Small-Numbered Languages of Russia”, carried out by the Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the number of speakers of Eastern Khanty is approximately 1000 people. According to the estimates of Andrei Filchenko, an expert on Eastern Khanty, in the early 2000s the breakdown was as follows: the Yugan sub-dialect of the Surgut dialect - approximately 500 speakers, the Vakh sub-dialect of the Vakh-Vasyugan dialect - approximately 50 speakers, the Vasyugan sub-dialect of the Vakh-Vasyugan dialect - approximately 20 speakers, the Aleksandrovo sub-dialect of the Vakh-Vasyugan dialect - approximately 20 speakers.

I.2.2. Age of speakers

Eastern Khanty is divided into three dialects: Surgut, Vakh-Vasyugan and Salym. The Vakh-Vasyugan and Surgut dialects are each divided into several sub-dialects. The Salym dialect is considered extinct, the number of speakers of the Aleksandrovo and Vasyugan sub-dialects of the Vakh-Vasyugan dialect is 10–20 people each. The Vakh sub-dialect of the Vakh-Vasyugan dialect and the Surgut dialect are relatively stable. The age of speakers varies greatly even within one dialect: for example, the number of speakers of Vakh is now approximately 50, and it is mainly preserved primarily by the older people, but in the most remote village of Korliki in the upper reaches of the Vakh, the language (in 2010s) was spoken by all generations, including children.

At least some sub-dialects of the Surgut dialect are still spoken by children, and among the speakers of older generations you can find those who speak it much better than Russian.

Although state support is insignificant, Khanty is one of the few languages for which there is an excellent tradition of publishing educational materials (textbooks, primers, teaching aids, school dictionaries, anthologies) in several dialects, including the two eastern ones, Vakh-Vasyugan and Surgut.

I.2.3. Sociolinguistic characteristics.

I.2.3.1. Threat of extinction

Eastern Khanty can overall be described as critically endangered. But if we look at individual dialects, the level of vitality will differ significantly. Of the three dialects (Surgut, Vakh-Vasyugan and Salym), Salym has already disappeared. This is explained by the fact that the basin of the left tributary of the Ob, the Salym, is quite small and located in a triangle formed by two large rivers, the Ob and the Irtysh, along which the Russian-speaking population settlements advanced in Western Siberia. Vasyugan and Alexandrovo Khanty are separated from the main territory of the Ob-Ugric peoples, the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Area, by administrative boundaries: their traditional territories (the Vasyugan and Ob basins) belong to the Tomsk region.

These two dialects have also practically disappeared (it was mentioned above that back at the beginning of the 21st century, the number of speakers of each dialect did not exceed 20, and those were middle-age to elderly people no younger than 50 years old).

Among the Surgut Khanty, a high level of language proficiency is still observed (you can find native speakers of Surgut Khanty who speak Khanty better than Russian). Both among the Vakh and Surgut Khanty there are families in which children speak their native language, evidence of the language being passed on from older to younger generations (the viability of the language is ensured primarily by the natural use of the language in the family and the transmission of the language from parents to children). However, the preservation of intergenerational transmission is, unfortunately, not the only factor influencing language prospects; the total size of the ethnic group is no less important. Considering that the Vakh Khanty as a whole are a rather small group, it is obvious that the number of families in which children still speak the language is very small. The figures for Surgut Khanty are more optimistic: the ethnic group is about 700 people, and around 500 of them speak their native tongue.

I.2.3.2.

Use in various fields

|

Area

|

Use

|

|

Family and everyday communication

|

Yes

|

|

Education: kindergartens

|

subject

|

|

Education: school

|

subject

|

|

Higher education

|

subject (?)

|

|

Education: language courses/clubs

|

Yes

|

|

Media: press (including online publications)

|

No

|

|

Media: radio

|

No

|

|

Media: TV

|

No

|

|

Culture (including existing folklore)

|

Yes

|

|

Literature in the language

|

Yes

|

|

Religion (use in religious practices)

|

Yes

|

|

Legislation + Administrative activities + Courts

|

No

|

|

Agriculture (including hunting, gathering, reindeer herding, etc.)

|

Yes

|

|

Internet (communication/sites in the language, non-media)

|

Yes

|

2.4. Information about a writing system (if applicable)

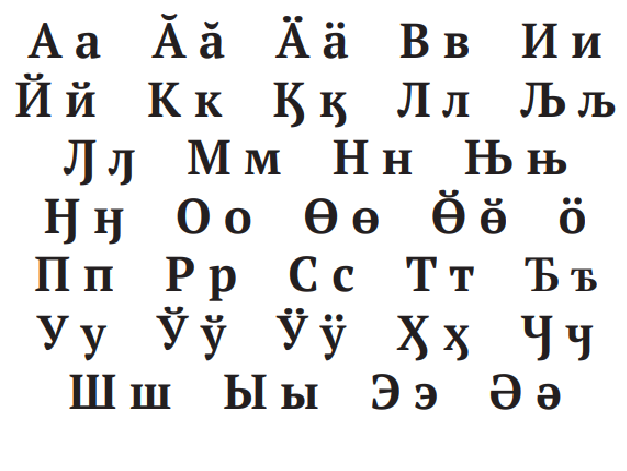

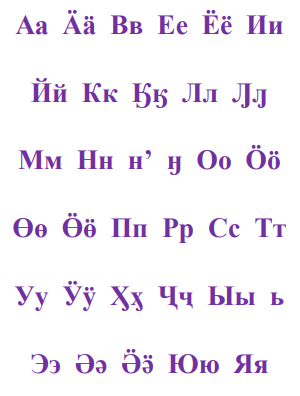

Alphabet of the Vakh sub-dialect of Eastern Khanty

Eastern Khanty currently uses two alphabets: Surgut and Vakh. You can read about the history of Khanty writing here {https://ouipiir.ru/node/18}.

Resources that allow you to type in Khanty on a computer and mobile device (the styles of some letters differ from the alphabets):

- virtual Khanty keyboard: http://hantyiskaya.klaviatura.su/

- development of layouts for computers and mobile devices:

https://habr.com/ru/news/t/650965/

or

https://tass.ru/sibir-news/9733855

.

Alphabet of the Surgut dialect of Eastern Khanty

Alphabet of the Vakh dialect of Eastern Khanty

I.3. Geographical characteristics:

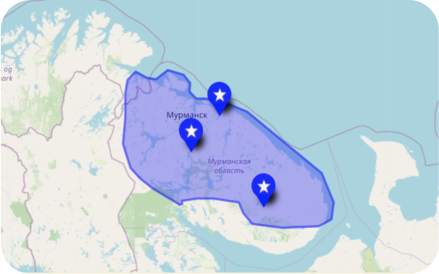

I.3.1. Constituent entities of the Russian Federation with ethnic communities

Speakers of Eastern Khanty live predominantly in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Area and in the north of the Tomsk region.

I.4. Historical dynamics

The historical dynamics regarding the size of an ethnic group (and the number of speakers of its language) is assessed primarily based on the data from population censuses conducted in Russia since the end of the 19th century. However, in the case of the Eastern Khanty and their language, this is difficult to do: in all censuses, the Khanty were counted together: no division into geographically separate ethnographic groups was carried out. One can only obtain data on the total number of the Khanty.

In 1897, 19,663 people were registered as the Khanty (Ostyaks). During this period, the majority of the Northern and Eastern Khanty could be assumed to be able to speak their native language. The censuses of the second half of the 20th century (1959-1989) show that the number of Khanty speakers is gradually decreasing: although the total number of the Khanty due to natural population growth during this period increased from 19 thousand to 22.5 thousand people, the number of those who indicated Khanty as their native language remained approximately the same and even decreased slightly, from 14.5 thousand to 14 thousand people.

In the 21st century, the number of the Khanty is still increasing: in 2002, 28,678 people were registered as the Khanty, in 2020 - 30,943, and approximately 13.5 thousand people indicated Khanty as their native language in 2002. Yet in 2020 there were only 11.5 thousand such respondents. At the same time, in the census of 2010, in addition to the question about what language the respondent considers to be his/her native language, a question about language proficiency was added, and approximately 9.5 thousand responded “proficient” in 2010. Of these 9.5 thousand, about 1,800 are Eastern Khanty: one can see that this number exceeds the above estimates, since experts attempt to estimate the number of people who have a perfect command of the language, whereas in reality the question about language proficiency can be answered as “proficient” even by those who have a fairly limited command of the language.

II. Linguistic data

II.1. Position in the genealogy of the world languages

The closest relatives of Eastern Khanty are, of course, Northern Khanty and Southern Khanty (disappeared in the 20th century). However, the differences between these three languages are quite profound.

The most striking distinctions are:

-

In Eastern Khanty there are fifteen (Vakh-Vasyugan) to twelve-thirteen (Surgut) or eleven (Salym) vowels, in Southern Khanty eleven or twelve, in Northern Khanty dialects - eight or nine.

-

In Eastern Khanty (Vakh-Vasyugan and Tromyogan) vowel harmony has been preserved (that is, all vowels in a word must be either front: i, e, ä, ö, ü, or non-front: i̮, a, o, u, etc.). d.). Neither of the two other languages has this system.

-

In the Ob-Ugric languages, non-initial syllables may contain significantly fewer vowels than the initial syllables. The set of vowels of the non-initial syllables differs significantly for those Khanty dialects in which harmony has been preserved (in Vakh-Vasyugan there are six such vowels, in Tromyogan eight) and for those in which vowel harmony has been lost (in the dialects of Southern and Northern Khanty the number of vowels of the second syllable is only three or four, since with the loss of vowel harmony there is no need to assimilate the vowels of the non-initial syllables to the vowel of the initial syllable).

-

In Vakh and Vasyugan Khanty, the verb has four past tense paradigms, in Surgut and Salym there are two (one of which is used but rarely), and in Northern and Southern Khanty there is only one.

-

In Eastern Khanty there are about eight cases, in Southern Khanty four or five, in Northern Khanty three or four.

-

In Northern Khanty there are special verb forms that describe an action that the speaker has not witnessed personally having obtained the information from some indirect signs (for example, by footprints in the snow) or from other people. In Eastern Khanty and in Southern Khanty, such meanings cannot be expressed grammatically.

This brief overview allows us to note that in almost all cases, Eastern Khanty had more of everything than Southern or Northern Khanty: more vowels, cases, and verb tenses. In some cases, such “abundance” was caused by the individual development of Eastern Khanty. But often it is evidence of more archaic features retained in Eastern Khanty and lost in Southern and Northern Khanty. Therefore, Khanty scholars often rely on the Eastern Khanty material as it is believed that it is more similar to Proto-Khanty than the other Khanty languages (Proto-Khanty was the language that gave birth to the three modern Khanty languages. Scholars obtain information about Proto-Khanty by comparing the material of the three Khanty languages).

The Khanty languages are grouped together with the Mansi languages (of the four Mansi languages, two are currently preserved: Northern and, to a limited extent, Eastern). Incidentally, of the three Khanty languages, Eastern Khanty is also most similar to the Mansi language, which also confirms its archaic nature. The Khanty and Mansi languages form the Ob-Ugric branch. Their closest genetic (but not geographic!) relative is the Hungarian language, and together they form the Ugric group of the Uralic family of languages.

You can read more about the Uralic language family

here

.

The Uralic languages are mainly found to the west of the Ural Mountains. Besides the Ob-Ugric languages, the Uralic languages are represented in Siberia only by the Samoyed languages (https://www.krugosvet.ru/enc/gumanitarnye_nauki/lingvistika/SAMODISKIE_YAZIKI.html) Samoyeds are the next-door neighbors of the Ob Ugric peoples, however, their languages are currently very far removed from each other (and of course, not mutually intelligible). Historically the period of their independent development has been very long and dates back thousands of years. Still, some Ob-Ugric and Samoyed languages did come into close contact with each other much later. The Vakh and Vasyugan dialects were in contact with some Selkup dialects: Northern Selkup [ссылка на статью атласа], now widespread on the Vakh and Turukhan rivers, and Tymsky, widespread in the Tym River basin.

On the northern border of the area, especially in the River basin of the Agan, the Eastern Khanty are neighbors to the Agan Nenets. Eastern Khanty had a significant influence on Forest Nenets [link to atlas article]. This influence is manifested in lexical borrowings from Eastern Khanty, as well as in the modeling of the Forest Nenets vowel system on Eastern Khanty, as indicated by Tapani Salminen, a Finnish expert on tundra and Forest Nenets: in Forest Nenets, a long/short opposition is formed for all vowels of the first syllable, the number of vowels possible in the non-initial (unstressed) syllables is significantly reduced, and a change in the root vowel begins to be manifested in the formation of grammatical forms of the word (in Forest Nenets the infinitive 'sit down' is

ng

a

mchosh

, but 3rd person singular 'he sat down' is

ng

y

mty

).

2. Eastern Khanty: internal dialectal division.

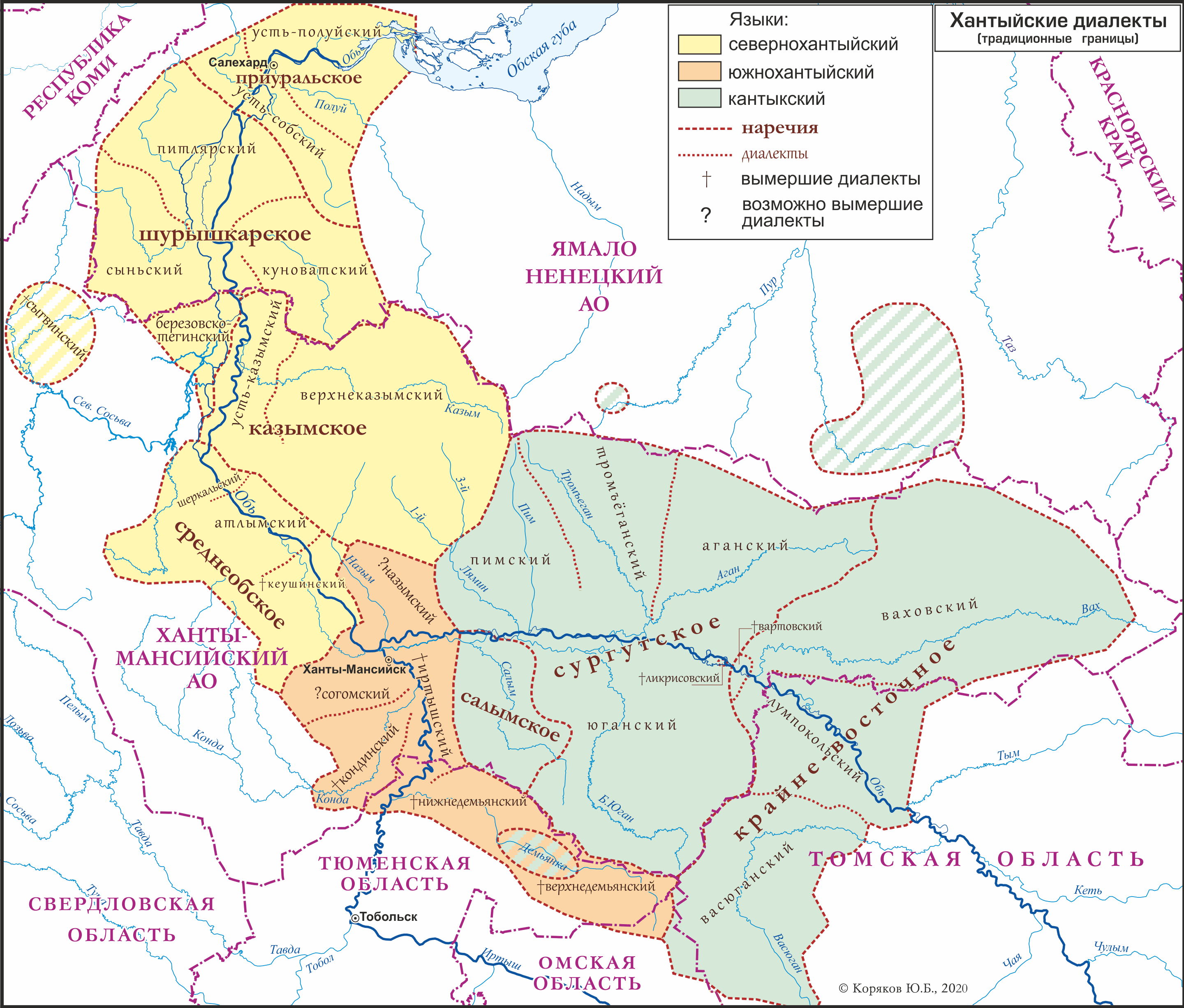

It has already been mentioned how heterogeneous Eastern Khanty is, but here the internal division of Eastern Khanty will be covered in more detail. The Eastern Khanty language is divided into dialects, which are further sub-divided into sub-dialects. Figure 1 shows the traditional area of distribution of the three Khanty languages, with Eastern Khanty highlighted in green.

The boundaries and names of individual dialects also appear on the map, the extinct dialects are marked with a special sign (see the legend). On this map, the Aleksandrovo sub-dialect of the Vakh-Vasyugan dialect of the Eastern Khanty language is designated as Lumpokol.

Figure 1. Khanty languages.

3. Brief history of academic research of the language

In the second half of the 19th century, the vocabulary of the Eastern Khanty and Southern Khanty dialects was recorded by Hungarian scholar Karoly P

á

pai. The lexical data on the material culture of the Eastern Khanty were collected at the end of the 19th century by Hungarian scholar Janos Janko and published by Marta Chepregi. The field diaries of Finnish scholar Uuno Taavi Sirelius, containing a Khanty-German dictionary (the Vakh and Vasyugan dialects), were published by the Finno-Ugric Society in Finland. At the beginning of the 21st century this dictionary was translated into Russian by Nadezhda Lukina. At the end of the 19th century, the vocabulary of the Vakh (and to a lesser extent Surgut) dialect was collected by Alexander Dunin-Gorkavich. In the second half of the 19th century, a comprehensive work on Eastern Khanty (phonetics, grammar, vocabulary, folklore texts) was carried out by Finnish scholars Kuusta Karjalainen and Heikki Paasonen. In the 20th century, the collection of texts in the Vasyugan and Vakh dialects was carried out under the leadership of Wolfgang Steinitz. His student was Nikolai Tereshkin, the first Khanty scholar who collected material on several dialects of Eastern Khanty and prepared a description of the Vakh dialect and a dialectological dictionary of Eastern Khanty. In the 1950s, material on the Vakh dialect was collected by Hungarian linguist Janos Gulya, who worked in Leningrad with students of the Institute of the Peoples of the North. In the 1970s, Eastern Khanty was also studied in Leningrad by Hungarian scholar Lazslo Honti. A lot of materials on Surgut Khanty were collected by Hungarian scholar Marta Chepregi; the texts she collected form the basis of the Surgut Khanty corpus. In the 1960s, materials on Vasyugan Khanty were collected by L. Kalinina at the Department of Languages of the Peoples of Siberia at the Tomsk Pedagogical Institute. Later, the study of Vasyugan Khanty was continued at this department by Olga Osipova. Eastern Khanty is currently studied in several academic institutions in Russia: the Department of Languages of the Peoples of Siberia at the Tomsk Pedagogical Institute, primarily under Andrei Filchenko. In the last few years, several expeditions to the Vasyugan, Vakh and Aleksandrovo Khanty were carried out by the faculty of the Tomsk Institute. The Surgut dialect of Khanty is studied at the Institute of Philology of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences under Natalya Koshkareva. Academic and applied study of Eastern Khanty and the preparation of teaching aids and folklore anthologies are carried out at Ob-Ugric Institute of Applied Research and Development in Khanty-Mansiysk.

4. Vocabulary

The vocabulary of Eastern Khanty reflects the contacts of the language with other ethnic groups. For example, the words

ilək, ilək, ilk

ӓk

'sieve' are borrowed from the Turkic languages, the words

p

ӓspə̈rt, pasprərt

'passport',

pasipa

'thank you', etc. are borrowed from Russian (the borrowings from Russian, of course, are much more recent than the borrowings from the Turkic languages). The contacts between the Eastern Khanty and the Selkup reveal a more complicated situation: it is often possible to find a word common to Eastern (more precisely, Vakh and Vasyugan) Khanty, Northern Selkup and the Tym dialects of Southern Selkup, but it might have no correspondence in any other dialects of Eastern Khanty or Northern Khanty, nor in the other dialects of the Selkup or the Samoyed languages. In this case, the word is represented only in a very narrow geographical area, and its absence in related languages does not allow us to establish whether it (and other such words) was borrowed by Eastern Khanty from Selkup or vice versa. Some examples are: Eastern Khanty

ӓni

, Selkup

ēńa

‘elder sister’, Eastern Khanty

ə

γsəl

, Selkup

āk͔səl

‘mushroom’. Contacts between languages can manifest not only in the borrowing of vocabulary, but also in the development of a completely identical set of meanings in words. This is clearly seen in the example of kinship terms, a closed group of words with clear oppositions. For example, in Vakh Khanty, the term

iki

, which in other Khanty dialects can mean

father-in-law

(father of the wife),

older brother

of

the father

or

mother

,

older brother

of the husband

, has come to also mean

grandfather

(paternal or maternal),

father-in-law

(husband's father) and

wife's older brother

. As a result, this term now designates the same set of older relatives which in Selkup is designated by

ilcha

: there is no doubt that in Vakh Khanty additional meanings for the term

iki

developed under the influence of the Selkup word.