Tundra Enets

Sociolinguistic Data

1. Existing Alternative Names

There are no generally accepted alternative names for the Tundra Enets language in Russian. There is an outdated name “the language of the Yenisei Samoyeds”, but it refers both to Tundra Enets and its cognate language, Forest Enets. Yet the Forest and Tundra Enets never considered themselves to be a single people: they had different self-names and never used them to call the Enets belonging to another ethnic group: for that, they used other ethnonyms. In the same way, the Samoyed peoples neighboring the Enets (Tundra Nenets and Nganasans, whose languages are related to Enets) never regarded the Forest and Tundra Enets as one people and also used different ethnonyms for them. Since in all the above-mentioned Samoyed languages (Tundra Nenets, Nganasan, Tundra Enets, Forest Enets), the name of the language is formed based on an ethnonym, the language of the Tundra Enets in all these languages is a different word than the one for used to designate the language of the Forest Enets.

Table 1 lists the names for the Tundra and Forest Enets (the peoples and the languages they speak) existing in these languages:

Table 1.

|

Language:

|

Names:

|

|

Tundra Enets

|

Tundra Nenets language

|

Forest Enets

|

Forest Enets language

|

|

Tundra Enets

|

somatu

|

somatu nau

|

pee bae

|

bae nau

|

|

Forest Enets

|

madu

|

madu baza

|

pe bai

|

bai baza

|

|

Nenets

|

mando

|

mando vada

|

vai

|

bai vada

|

|

Nganasan

|

səmaɁtu

|

səmatu buoӡu

|

bau

|

bai buoӡu

|

The term “Enets” (as well as “Nenets”, and “Nganasans”), although based on Samoyed words, was introduced somewhat artificially by ethnographers in line with the new ethnic and linguistic policy, when the ethnographic terms of the “era of tsarism” were being replaced by artificial “self-names”. A wave of re-labeling swept across many ethnic groups: the Yuracs began to be called Nenets, the Yenisei Samoyeds - Enets, the Tavgi - Nganasans, the Ostyak-Samoyeds - Selkup, the Yenisei Ostyaks - Kets, the Goldi – Nanai, the Votyaks - Udmurts, the Voguls - Mansi, etc.

2. General Characteristics

2.1. The Number of Native Speakers and the Corresponding Ethnic Group

It is challenging to estimate the number of speakers of Tundra Enets based on the census data: the censuses have never divided them into separate ethnographic groups, and both the Forest and Tundra Enets were counted together. In the census of 2010, 227 people called themselves Enets (without further division into the Forest and the Tundra), of whom 102 called Enets their native language. At the same time, in the census of 2010 (which had an added question about native language proficiency), only 43 people answered positively. But it must be remembered that a positive answer to the question about language proficiency remains a subjective decision of the respondent: even those who speak the language to a very limited extent can still answer positively. For example, it might be the people who can construct a small set of fairly simple phrases yet never really use the native language, communicating exclusively in Russian.

2.2. Age of Speakers

Young people and children do not speak the ethnic language and there are practically no native speakers left among the middle generation. Even in the early 1990s, that is, thirty years ago, only several very elderly people and children spoke the language perfectly. Now the use of the language is limited to a communicative situation arising between native speakers and language researchers: Tundra Enets is no longer used as a language of communication

2.3. Sociolinguistic Characteristics

2.3.1. Threat of Extinction

The Tundra Enets language is close to extinction. As mentioned above, its transmission to the younger generation has stopped, thus doing away with the only factor ensuring the viability of a language. It is very difficult to maintain a language that one did not learn in childhood. Native languages all over the world are faced with a similar situation: the pressure of the foreign language environment, and the influence of the administratively dominant language (used in education, shops, hospitals, and state institutions) leads to the fact that even the people who are quite fluent in their native tongue switch to the socially more prestigious language, they start speaking it at home and addressing the children in it. Special measures are needed to support small-numbered languages. Moreover, the initiative must come from both sides: from the state and from the linguistic community.

2.3.2. Use in Various Fields

|

Area

|

Use

|

|

Family and everyday communication

|

Extremely rarely

|

|

Education: kindergartens

|

No

|

|

Education: school

|

No

|

|

Higher education

|

No

|

|

Education: language courses/clubs

|

No

|

|

Media: press (including online publications)

|

No

|

|

Media: radio

|

No

|

|

Media: TV

|

No

|

|

Culture, (including existing folklore)

|

Extremely rarely

|

|

Literature in the language

|

No

|

|

Religion (use in religious practices)

|

No

|

|

Legislation + Administrative activities + Courts

|

No

|

|

Agriculture (including hunting, gathering, reindeer herding, etc.)

|

limited

|

|

Internet (communication/sites in the language, non-media)

|

No

|

2.4. Writing System

Officially, only Forest Enets has a writing system, but theoretically it can also be used for Tundra Enets.

3. Geographical Characteristics

3.1.

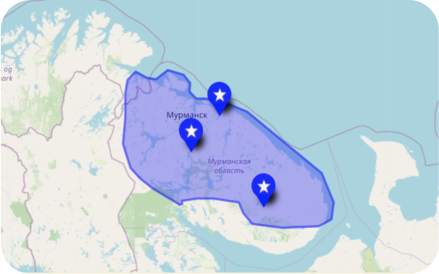

Constituent Entities of the Russian Federation with Ethnic Communities

Speakers of Tundra Enets live on Taimyr (Dolgan-Nenets Autonomous Area). Several native speakers live in the village of Vorontsovo (the only Tundra Enets native community), and several, according to Olga Khanina and Andrei Shluinsky, roam the Tukhard tundra with the Nenets. By the beginning of the 20th century, the territories of the nomadic Tundra Enets extended from the right bank of the Yenisei Bay in the west to the Nganasan territories in the east. According to Boris Dolgikh, the Tundra Enets migrated to these territories in the 17th–18th centuries from the south.

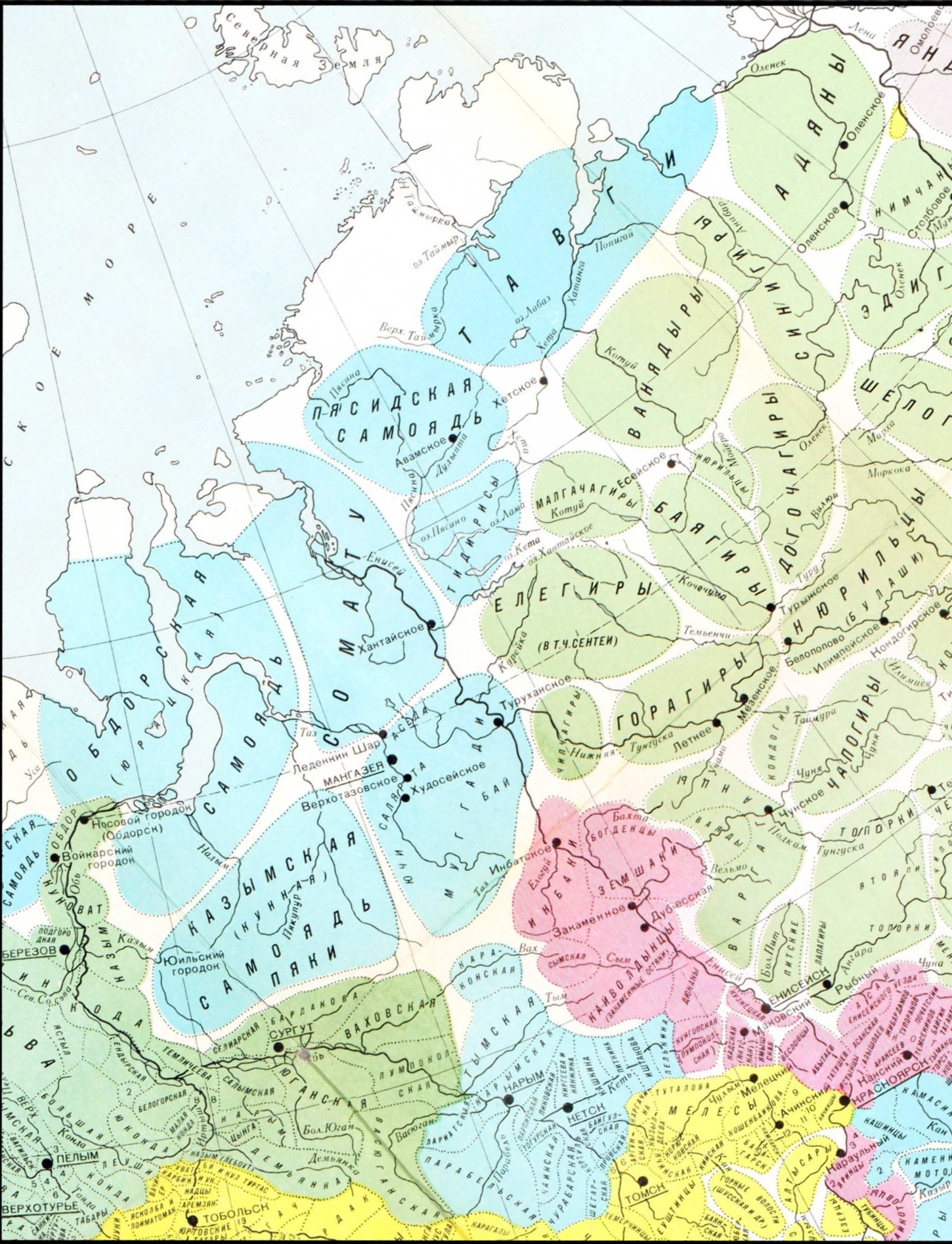

The three maps below show the migration routes and the reduction of the ethnic territories associated both with the steady decrease in the total number of Tundra Enets throughout the entire historical period and, ultimately, with their transfer to sedentary life in the 1960s.

The first map was compiled by Boris Dolgikh. It is a reconstruction of the settlements of the peoples of Siberia in the 17th century according to the yasak (tax) documents of the Russian administration of Western Siberia. Tundra Enets here are called “somatu.”

Map 1

Map 2, compiled by Olga Khanina, Andrei Shluinsky and Yury Koryakov, shows the roaming territories of the traditional nomads of the Tundra Enets at the beginning of the 20th century (according to Evgeny Khelimsky, the Tundra Enets had abandoned the right bank of the Yenisei by the middle of the 19th century).

Map 2

Map 3 shows a fragment of the map compiled by Yury Koryakov. It shows the modern settlements of the small-numbered peoples: three Enets locations (the northernmost is the Tundra Enets village of Vorontsovo, the southernmost the Forest Enets village of Potapovo, with the regional center, the city of Dudinka, located in between). Dudinka is a place of residence of both Forest and Tundra Enets.

Map 3.

3.2. Total Number of Traditional Native Settlements

There is one single Tundra Enets native village.

3.3. List of Settlements

The village of Vorontsovo on the right bank of the Yenisei Bay, beyond the Arctic Circle, has been the main place of native residence of the Tundra Enets after they settled down in the 1960s.

4. Historical Dynamics

It is difficult to estimate the number of speakers of Tundra Enets based on census data, for the following reasons. Firstly, the two Enets ethnic groups were counted together. Secondly, the Enets only appeared as a separate ethnic group for the first time in the census of 1989, even though they might have been one of the first Samoyed peoples that the Russians encountered in the Yenisei basin: according to Evgeny Khelimsky, the name of the Russian trading city of Mangazeya, founded in 1601 on the Taz, comes from the Nenets version of the name of one of the Enets clans: in Enets, this clan is called Mogadi, in Nenets

Mangazi

.

It is possible to obtain some information about the population of the Siberian peoples indirectly, based on the documents of the Russian administration that established itself in the Siberian territories after they had become part of the Russian Empire. According to the calculations of Boris Dolgikh, based on the analysis of yasak documents, in the 18th century, the number of Tundra Enets was about 800 people (the group of Forest Enets was approximately half as small); during that period, they all spoke their native language. Evgeny Khelimsky notes that by the middle of the 19th century, the number of both Enets groups decreased to approximately 500 people, that is, by more than half. There were several reasons for this: the active development of the Enets’ northern territories adjacent to the Yenisei by the Russians; the resettlement of a number of ethnic groups (Forest and Tundra Enets, the Northern Selkup, Tundra Nenets), provoked by the Russian expansion, which resulted in both assimilation processes and military clashes. One must not forget the epidemics of the diseases that the indigenous peoples had not encountered before the arrival of the Russians. The following statistical data belong to the end of the 20th century (the census of 1989). This census recorded only 209 people as Enets (without dividing them into Forest and Tundra). In 2002 there were 237 Enets, in 2010 – 227. In 1989, 110 people indicated proficiency in their native language, in 2002 – 119. In 2010, 102 people named Enets as their native language, but only 43 people indicated linguistic proficiency (the scholars estimate the real number of native speakers to be three to four times less). Thus, at the end of the 20th - beginning of the 21st centuries, the number of both groups of the Enets was stable, slightly exceeding 200 people. This means that the number of Enets has decreased approximately six times since the 17th century.

II. Linguistic Data

1. Position in the Genealogical Classification of World Languages

Tundra Enets belongs to Samoyedic languages. The Forest Enets language is the closest to it, and Tundra Nenets, Forest Nenets and Nganasan are linguistically somewhat removed. All these languages belong to the North Samoyedic subgroup, this name reflecting the territories of their modern distribution. Another language belonging to the Samoyedic group is Selkup. Samoyedic languages, together with Finno-Ugric languages, form the Uralic language family.

The Uralic language family occupies vast areas of Eurasia: the easternmost representatives are Samoyedic languages, and the westernmost are Estonian, Finnish and Hungarian.

2. Basic Linguistic Information

Phonetics

Of all the Northern Samoyedic languages, Tundra Enets can perhaps be called the most melodic: if we compare the words of Tundra Enets with the words of Forest Enets, Nganasan and Nenets, it turns out that, informally speaking, in Tundra Enets there are more vowels per consonant than in the words of all the other Samoyedic languages. The words of Tundra Enets are the most vowel-rich. This is due to several factors. Firstly, in Tundra Enets, in contrast with Forest Enets and Nenets, vowel sequences are preserved, as in the words ‘birch’ or ‘sleeve.’ Secondly, in Tundra Enets new vowel sequences are formed due to the loss of intervocalic -ng- or -m-, as in the words 'layer' or 'bone marrow' (these consonants also drop out in Forest Enets, but, unlike in Tundra Enets, the resulting vowel sequences are simplified and shortened). Thirdly, in Tundra Enets, unlike in Forest Enets and Tundra Nenets, the word-final vowel is always preserved. In Nenets and Forest Enets, a whole series of such vowels are dropped, as in the words ‘tribe, ‘sleeve’, and ‘layer.’ Fourthly, in Tundra Enets two consonants are never pronounced in a row: all the combinations of consonants that existed in Proto-Samoyed (the common ancestor of all Samoyedic languages, which existed about 2000 years ago) were simplified in Tundra Enets, but preserved in Nganasan, and Nenets, e.g. the words ‘horn’, ‘clan’, ‘overnight stop’. Such combinations were simplified in Forest Enets, but new sequences of consonants were formed as a result because some vowels in the middle position are not pronounced in Forest Enets (e.g. the word ‘several’ in Tundra and Forest Enets).

General Characteristics

Tundra Enets, like the other Samoyedic languages, has a rich morphology. All meanings, both inflectional and word-formative, are expressed by suffixes (there are no prefixes in Enets, nor in the other Samoyedic and Uralic languages).

Consonant System

The consonant system of Tundra Enets is quite rich. Several sounds not present in Russian deserve a special mention. Firstly, it is an interdental voiced [ð] (English this). In the orthography of Forest Enets, this sound is expressed by the Russian letter З, but pronounced completely differently, so here this sound will be represented as Ž (з̌ in the Nganasan alphabet). The diacritic indicates that this sound differs in pronunciation from the sound of the Russian letter З. The second sound, also absent in Russian, but existing in English (sing), is the back-lingual nasal [ŋ], which is represented as Ӈ in orthography. The third sound is the glottal stop, transcribed as [Ɂ], and represented with an apostrophe in the orthography. Here, the sign /Ɂ/ will be used, simply because graphically it is more “noticeable”. The glottal stop is not a phoneme in any of the languages familiar to most readers, but to get an idea, you can recall the English interjection Uh-oh where it appears between the two vowels and is clearly audible: after the first vowel is pronounced, the throat closes with an abrupt opening before the second vowel is pronounced.

Noun Morphology

The noun in Tundra Enets has three forms: singular, dual and plural: enecheɁ ‘man’, enechegoɁ ‘two people’, enecheoɁ ‘people.’

Tundra Enets has seven cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative-directive, locative, ablative and prolative. The cases are divided into two groups. The first group consists of the three most frequent cases: nominative, the case of the subject (enecheɁ diaža 'the person is walking'), accusative, the case of direct object (modi enecheoɁ soožižoɁ 'I saw a man'), genitive, the case of belonging (mežo ӈу ‘chum’s pole’; in Tundra Enets, the genitive case is always placed before the word indicating the owner). The second group consists of the four cases mainly expressing spatial relations: directional (surokodoɁ udya punga 'put meat in a bowl', metoɁ taežoɁ 'approached the chum’), locative (mekone adua 'sits in the chum') as well as instrumental (tiakhane kaneda 'rides (by means of) deer’, užakhane sebuta 'tears with hands'), ablative (expresses the place from which one leaves, from which something is taken out, etc.: kuroikhožo ožima 'climbed out of the sleeping bag', tuka kodohožo ožidi 'took out an ax from the sledge'), prolative (expresses movement along something extended: moraane dyaza 'walks along the (sandy) shore', kaita užione dyaža 'follows the trail of his companions’).

In the modern Tundra Enets, the final glottal stop is often not pronounced in these cases (in the field data of the 1970s we observe the same phenomenon, so this process cannot be explained by the decomposition of the Enets language system when its speakers switched to Russian). This leads to the fact that the stems with thematic vowels can produce as many as six coinciding case forms: nominative, accusative and genitive singular and plural (in the stems with thematic consonant, as we can see in the declension of the word meɁ 'chum', a complete coincidence does not occur due to the use of different stems in different cases: me-, mežo-, mežu-.

In the stems with thematic vowels, at least a partial difference in cases is preserved if the noun has a possessive suffix ('mine', 'yours', 'his/hers', 'ours', 'yours', 'theirs'). It results from the fact that the possessive indicator “preserves the memory” of the previous case indicator (the glottal stop); as a general rule, the combination of a glottal stop and the following word-initial consonant of the possessive suffix is simplified leading to a change in the initial consonant of the possessive suffix.

Verb morphology

In Tundra Enets, the verb agrees with the subject in person and number (just like it does as in many other languages, in Russian, for example). In the examples below, the verbal indicators of person and number are highlighted in bold (they are the suffixes similar to the Russian forms nes-u, nes-yom, nes-yote): modiɁ kani-žoɁ 'I left', ne kani-Ø 'the woman left', modinaɁ kani-baɁ 'we left', etc. But in Enets there are as many as five sets of such indicators of person and number.