Forest Enets Language

I. Sociolinguistic Data

1. Existing Alternative Names

For the Forest Enets, most scholar use such names as the Forest dialect of the Enets language, Bai dialect, Bai, Pe-Bai; Enets language without specification; the Yenisey Samoyed dialect, as a name for both Enets languages.

The self-designation of Forest Enets speakers is онɛй энчуу. The Enets ethnonym, by analogy with Nenets, was artificially introduced in the 1930s. It describes the native speakers of both Enets languages (Forest and Tundra, or Bai and Madu), even though these groups do not have a common ethnic identity. In the past, they also used such names, as Yenisei Samoyeds for native speakers of both Enets languages, as well as Karasin or Baishen Samoyeds for Forest Enets speakers. The autoglossonym of Forest Enets is онɛй база.

Traditionally, Forest Enets and Tundra Enets are considered as 2 dialects of a single Enets language. They are indeed mutually intelligible: their native speakers can understand each other, even when they speak their idioms. At the same time, these two idioms have considerable phonetic and lexical differences, including the most common vocabulary and even personal pronouns. The affinity of Forest and Tundra Enets languages results from their secondary rapprochement due to intensive contact in the 19th century.

2. General Characteristics

2.1. Number of Native Speakers and the Corresponding Ethnic Group

The 2010 census provided the following numbers: 102 respondents designated Enets as their mother tongue, without any differentiation between Forest Enets and Tundra Enets, whereas 43 people indicated their proficiency in Enets. Therefore, most of the respondents interpreted this question as the one about the language of their ethnos, not the one they learned naturally in childhood.

Linguists estimate that there are no more than 30 people who master Forest Enets to varying degrees, which, in a certain sense, is an even more optimistic estimate than the Census results (since the Census did not differentiate between Forest Enets and Tundra Enets and there are up to 20 people who master Tundra Enets to some degree). However, it should be taken into account that there are only about 10 people who are fully proficient in Forest Enets (i.e. their proficiency is comparable to that of the previous generation of speakers).

2.2. Age Structure of Native Speakers

All people proficient in Forest Enets are aged over 45, with the the majority being over 60-65 years old. The oldest speakers are aged over 75, but nobody is over 80, there are no older native speakers alive.

The most significant turning point in both the use and learning process of Forest Enets happened in the 1960s-1970s. During this period, on one hand, indigenous children often spoke Russian with older friends or siblings, who had already acquired the Russian language at school, even before it was their turn to go to boarding schools. On the other hand, it was typical of this period to have inter-ethnic reindeer herding teams, where Russian inevitably became the primary language of communication.

2.3. Sociolinguistic Characteristics

Speakers of Forest Enets live mainly in Potapovo and Dudinka of the Taimyr Municipal District, Krasnoyarsk Krai. Some of them spend a lot of time in the tundra in the vicinity of Potapovo.

Even native speakers proficient in Enets very rarely use it in their daily communication. As long as their parents’ generation was alive (i.e. until the beginning of the 21st century), they used Forest Enets to communicate with them, but once it was gone, Forest Enets now tended to speak Russian at home. The transmission of Forest Enets to the following generations has been interrupted, neither young adults nor children are able to speak it.

In recent years, a language study group was created in the Potapovo nursery school. It allows children to discover their ethnic language, if only to a small extent. Nonetheless, the language remains a vital component of self-identification for many Forest Enets, and the use of it, even if it is just some words, is highly important.

Vitality Status

1В — dormant.

Regular communication in Forest Enets ceased by the beginning of the 21st century when the parents of current native speakers passed away. Ever since then, its use in communication has been irregular, and the situations that would require it occur less and less often as the number of speakers continues to decrease.

Regular transmission of language to children ceased by the 1970s.

Preschool education: in the early 2010s, Forest Enets language courses were launched in a nursery school in Potapovo within the framework of an experimental language nest project (when minority language becomes the main language of communication with children).

School education: Forest Enets is taught as a separate subject in the secondary school in Potapovo. In the 1990s, it was optional. In the noughties, it became an obligatory course for all secondary school students of the village as a regional component of school education. Later, the teaching of Forest Enets at school was suspended due to the integration of the regional component of education into the general program of the Krasnoyarsk Krai. But then it was reintroduced as an obligatory course for elementary schools and an optional one for secondary schools. At present, it is an optional course for both elementary and middle schools.

Secondary vocational education: Forest Enets was taught as a separate course in the Taimyr College (vocational school) in the 1990s and the noughties (taught by D. Bolina, N. Borisova, as well as Z. Bolina as a substitute). Later, these courses were suspended due to the lack of teachers.

The following teaching materials are available for Forest Enets:

-

Enets-Russian and Russian-Enets school dictionary;

-

a collection of Enets texts in both Enets languages for the general reader;

-

a collection of Enets texts in both Enets languages with a popular grammatical description for the general reader;

-

Enets-Russian phrasebook;

-

ABC and a corresponding workbook;

-

preschool reading books;

-

Enets image thesaurus, including educational texts.

The Enets supplements to the Taimyr newspaper were also used as learning aids for teaching Forest Enest at school.

There is no non-fiction literature written in Forest Enets.

There is no long-form fiction in Forest Enets. Most of the written creations in the native language are songs (written by Viktor Palchin, Svetlana Roslyakova, Zoya Bolina, etc.) destined, above all, for oral presentation. There are also some short poems. Galina Bolina translated Charushin’s short stories into Forest Enets.

Although the Enets pages in the Taimyr newspaper are categorized as the use of language in the press, in reality, these are opinion pieces. Эззуй. След Нарты [Ezzui. Traces of a sleigh] (2014) by Zoya Bolina belongs to the same category.

In 1990-2003, there used to be an Enets radio program (edited and hosted by N. Bolina, and for a short time N. Borisova), aired once a week as part of radio broadcasting in Taimyr national languages. In addition to the materials prepared by the editor, it broadcasts numerous interviews with Forest and Tundra Enets, as well as monologues recorded by native speakers of both languages. At present, there are no radio programs in Enets due to the absence of a qualified editor, but sometimes they broadcast Enets recordings within the Nenets radio programs.

Occasionally, Forest Enets is used in amateur plays staged in Potapovo, as well as folklore festivals in Dudinka (it used to be more popular in the 1990s).

Forest Enets is not widely used in religious rituals. Presumably, Forest Enets was traditionally used in the practice of shamanic cults, but there is only circumstantial evidence of this. In 1995, there was an experimental publication of the Forest Enets translation of fragments of the Gospel of Luke by D. Bolina, but it never caught on.

2.4.

Information on the Writing System

The first version of a Cyrillic-based Forest Enets alphabet was published in 1986 by N. Tereschenko.

Starting from the 1990s, there have been numerous publications in Forest Enets, recorded with a Cyrillic-based alphabet and designed for a broad audience (key authors: K. Labanauskas, D. Bolina, Z. Bolina). These publications used both Russian and Nenets orthographies, they also suggested and tested additional symbols to reflect the sounds that do not exist in other languages. On the other hand, they did not provide any unified and/or consistent orthographic system.

The most recent version of the alphabet and orthographic recommendations was approved at the seminar of the working group for the creation of the Enets system of writing that took place in Dudinka in October 2019.

In particular, they approved the following additions to the Russian alphabet:

ɛ – open front vowel;

ô – closed back vowel;

ӈ – backlingual nasal consonant;

” – glottal stop.

Taking into account the use of all Russian letters to convey the non-adapted borrowed words, the Enets alphabet includes 37 letters:

а, б, в, г, д, е, ɛ, ё, ж, з, и, й, к, л, м, н, ӈ, о, ô, п, р, с, т, у, ф, х, ц, ч, ш, щ, ъ, ы, ь, э, ю, я.

These orthographic solutions were used, for example, in the ABC by D. Bolina, published in 2019.

The scientific literature transcribes the examples of Forest Enets using Cyrillic, as well as numerous versions of Latin transcription.

Neither Forest nor Tundra Enets has any literary version. Forest Enets took upon itself certain functions of the literary language (Enets page in a newspaper, Enets radio broadcasts, Enets language courses, Enets-Russian and Russian-Enets dictionary for schools), but it is due to the fact that its native speakers are the only ones to carry out any outreach and educational activities. At the same time, the use of Forest Enets as a literary language has no official status.

3. Geographic Characteristics

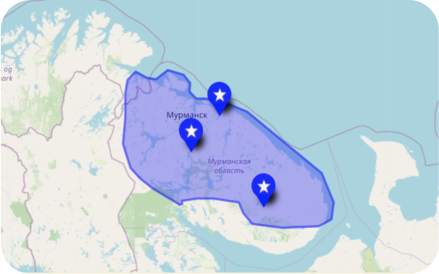

3.1. Constituent Entities of the Russian Federation with Ethnic Communities

At present, the overwhelming majority of Forest Enets speakers are concentrated in the southwestern part of the Taimyr Municipal District, Krasnoyarsk Krai, which previously (before 2007) used to be the Taimyr (Dolgano-Nenets) Autonomous Okrug, Krasnoyarsk Krai. Forest Enets have inhabited this territory at least since the 19th century.

Historically, the traditional territory of Forest Enets (Khantai Samoyeds, as they were called at the time) was somewhat further south (upstream along the Yenisei River) and extended beyond the modern Taimyr Municipal District. In the 17th century (when we begin to find some documentary records of Enets), about 500 Forest Enets used to roam in the area between the Taz and Yenisei rivers, from Nizhnyaya Tunguska and Kureika to the upper and middle course of the Taz River, on the territory that corresponds today to the southeastern part of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug and the northwestern part of the Turukhansky District, Kranoyarsk Krai. In the 17th – 18th centuries, Enets had military confrontations with Russians, Selkups, and Nenets, which resulted in them being pushed further to the north and east, losing a considerable part of their lands, and suffering a decline in numbers. During the 18th century, pushed by the Selkups arriving from the South, Forest Enets gradually moved northward, downstream along the Yenisei river, driving out Tundra Enets in their turn. In the second half of the 19th century, there were only about 500 Enets left. Already in the 19th century, some Forest Enets began to roam together with Tundra Enets and gradually switched to their language.

With the arrival of the Soviet administration, Forest Enets were assigned to the territory attributed to Potapovo, 80 km away from Dudinka upstream of the Yenisei River. Even today, Forest Enets still live in Potapovo, although some of them gradually moved to Dudinka.

3.2. Total Number of Traditional Native Settlements

Traditionally, Forest Enets were nomads and did not live in any settlements. However, the main locality associated with Forest Enets is the village of Potapovo. Today, Potapovo is included in Dudinka, an urban settlement, for administrative purposes. But in reality, it remains a rural settlement, which communicates with Dudinka via passenger ships Krasnoyarsk-Dudinka in summertime and by helicopters in winter.

In the Soviet period, Forest Enets were registered in Potapovo (and for a short time also in the no longer existing Nikolskoye), and today even those Enets who spend significant periods of time in tundra, associate themselves with this village.

Nowadays, there are probably even more Forest Enets speakers in Dudinka than in Potapovo. One can also find isolated native speakers in other settlements of Taimyr: Norilsk, Talnakh, Karaul, etc., as well as beyond it, in Krasnoyarsk and Saint-Petersburg.

2010 Census Data by Localities

|

2010 Census

|

Total population

|

Enets

|

Language proficiency

|

Mother tongue

|

|

Dudinka

|

22204

|

37

|

9

|

20

|

|

Potapovo

|

334

|

87

|

10

|

32

|

4. Historical Dynamics

The number of native speakers and corresponding ethnic group based on various censuses (starting from 1897) and other sources.

|

Census Year

|

Number of Native Speakers (men)

|

Size of Ethnic Group (men)

|

Comments

|

|

1897

|

1,326

|

—

|

Nganasans and Enets were counted together; but there are two possible interpretations: either the Yenisei Samoyed group included both Tundra and Forest Enets (then we can assume that Forest Enets account for approximately one quarter of the total), or only Tundra Enets (and in that case, Forest Enets were included with Nenets)

|

|

1926

|

—

|

—

|

Enets were probably included in Samoyed group together with Nenets

|

|

1937

|

|

|

counted among Nenets

|

|

1939

|

|

|

counted among Nenets

|

|

1959

|

|

|

counted among Nenets

|

|

1970

|

|

|

counted among Nenets

|

|

1979

|

|

|

counted among Nenets

|

|

1989

|

110

|

209

|

total of Forest and Tundra Enets; native speakers also include respondents who said that they were fluent, but their key language was different (for example, Russian)

|

|

2002

|

119

|

237

|

total of Forest and Tundra Enets

|

|

2010

|

43

|

227

|

total of Forest and Tundra Enets

|

II. Linguistic Data

1. Position in the Genealogy of World Languages

Ural family > Samoyedic branch > North Samoyedic group

The Forest Enets language belongs to the Samoyedic branch of the Ural language family. Within the Samoyedic group, it is the closest to Tundra Enets, and Nenets languages along with it. Traditionally, the Enets and Nenets idioms are attributed to the North Samoyedic group, along with Nganasan, although there exists an alternative point of view about the existence of a separate Nenets-Enets branch within Samoyedic languages.

Until the 1960s, researchers considered Enets to be a dialect of Nenets. It was only in the 1990s that the Forest Enets and Tundra Enets idioms began to be perceived as independent languages.

2. Dialects

There is only circumstantial evidence left as to the existence of dialects: there are certain differences in the parlance of members of different indigenous families. Interestingly, Forest Enets have no general self-designation, but every clan has one of its own, and even today’s Forest Enets, members of a particular family, identify themselves with it. It is highly likely that every clan had its own dialect or parlance in the past.