|

|

Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, Russian Academy of Sciences,

Svetlana Tyukhteneva

|

The Telengits. General Information: Endonyms, Ethnographic Groups, Population, and Settlement

The Telengits' endonym name goes back to the medieval term

tele

. This ethnonym has been known since the middle of the I millennium AD on the territory of modern Mongolia and the southern part of Siberian in Russia. For a long time, the ethnonym

tele

came and went, having nevertheless survived to this day in such names of South Siberian ethnic groups as

Telengits

,

Teleuts,

and

Teles

.

As an indigenous minority, the Telengits were officially included in the Unified List of Indigenous Peoples of the Russian Federation in March 2000.

According to the 2020 All-Russian Population Census, there were 2,769 Telengits in the Altai Republic, including 1,336 men and 1,433 women. In the country as a whole there are 2916 people, including 1412 men and 1504 women.

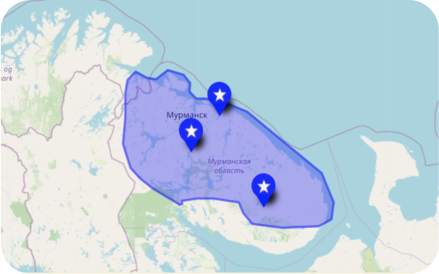

SETTLEMENT: Telengits, like other representatives of the indigenous population of the Altai Republic, are settled mainly in the territory of traditional residence. At the same time, compared to the 2010 census, the territory of their settlement has expanded significantly. According to the 2020 сensus, at least two hundred Telengits permanently live in the territories of various regions of Russia. A significant part of those involved in labor “commuting” migration, according to empirical data, work on a rotational basis in the regions of the north of Western Siberia and the Far East.

In Russian ethnology, Telengits are also known as

chuy kizhi

, which means “man from the Chuy River,” and

ulaan kizhi

, “man from the Ulagan and the Bashkaus rivers.” Currently, Telengits can be divided into two territorial-ethnographic groups. Some are settled in the Kosh-Agachsky,

chuy kizhi

, and Ulagansky,

ulaan kizhi

, districts of the Altai Republic. Quite a lot of Telengits also live in Gorno-Altaisk, the capital of the region. The modern Telengits do not call themselves

telengit kizhi

, since

kizhi

means “person,” and the question “Are you a person or not a person?” would sound off-putting. So, when asked about nationality, they simply say “Altai/Altaian” or “Telengit”.

The ethno-cultural identity of the Telengits is based on belonging to a patronymy called an

uya

(nest), followed by a

kezek

(branch of a large family), then by a

seok

(clan) subdivision (for example,

kara mool

), then by a

mool

(seok proper), and on to the territory of residence (for example, the mools of Ortolyk), then on to the local community along the river valley –

Chui ichinin telengidi

(“a Telengit from the valley of the Chuya”), then on to the administrative district (a native of Kosh-Agach, Ulagan, Gorno-Altaisk, etc.). The generic ethnic identity for the majority of the Telengits is the national component (an Altai/Altaian).

The modern settlement of the Telengits is characterized by their preservation of ancestral territories from the 19th - beginning of the 20th centuries. An often-overlooked, yet widely acknowledged fact is that the preservation of the exogamous institution of

seok

(from the Altai

s

ӧӧк

, literally “bone”) entails the marriage of a man and a woman from different

seoks

.

As a result, one settlement would always have representatives of different

seoks

, regardless of the subethnic or ethnic background of a given person. Consequently, among the residents of the Kosh-Agach and Ulagansky districts, along with the Telengits and Altaians, there are people from other areas, various

seoks

, and different identities.

Researchers Dmitry Funk, Agniezska Halemba, Valery Stepanov, Svetlana Tyukhteneva, and Vera Kydyeva demonstrated that belonging to a

seok

, as well as full knowledge of the maternal lineage of the clan (

taai söök

), remains an important part of the life of the Telengits. The line of kindred (clan) names recorded by researchers of the 19th - early 20th centuries is still preserved among the Telengits in full.

The emergence of new indigenous minorities, according to Dmitry Funk, looks like a chaotic process only at first glance. In fact, this process is largely determined by the complex and specific ethnic composition of all the Turkic-speaking groups in the region. This specificity lies in the fact that the smallest endonym-possessing ethnic unit in South Siberia, aware of its kinship and lineage, and occupying a compact territory, is a

seok

, or clan.

Similar processes of expansion, fragmentation, and re-unification are characteristic of the ethnic history of all the peoples of Central Asia. Clans were in constant motion with groups and branches separating from them and forming new clan communities, although their members still followed the basic rules of paternal lineage and exogamy. Such processes of permanent fragmentation and unification make it possible to understand how different Turkic-speaking peoples have been able to preserve the same medieval ethnonyms, and why peoples who once enjoyed certain statehood have been delegated to a lower social taxonomic unit, like a seok. According to Lev Lashuk, there is a certain pattern in the development of social relations among the medieval nomads of Eurasia: throughout the reconstructed historical period, they formed new associations on the basis of kinship, or to be more precise, on certain combinations of kinship, lineage, neighborhood, and citizenship.

In light of long-term interethnic contacts on the territories inhabited by the ancestors of the Altaians and Telengits, the bilingualism of the local population of the modern Altai Republic can also be seen as a historically determined phenomenon. According to the All-Russian Population Census of 2010, the native language situation breaks down as follows: out of 3.648 Telengits, 3.124 speak Russian, 3.480 speak Altai languages, and 97 speak the Kazakh tongue.