|

|

Dr. Kisser

Senior Research Fellow, Arctic Research Center, Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography,

Russian Academy of Sciences

|

Spiritual culture (mythological worldview, traditional beliefs, holidays and rituals)

The Ket religion was based on animism. According to their beliefs, every plant, animal and natural phenomenon had a vital principle manifested in the form of a spirit. The entire world was believed to be inhabited by them. Some of the spirits were neutral in relation to man (“stone”, “earth” and “sky” spirits). This category includes the following creatures:

Kaigus

, the master of all animals,

Kholai

, the mistress of all hunted animals, possibly the mistress of the forest,

Ulgys

, the master of waterways and fish (Alekseenko 1967: 170).

Es

was the supreme deity. He was an old bearded man living in the sky (the Kets did not wear beards), dressed in a wide white parka. Shamans call on to him, travelling to the “upper world”; ordinary people asking for help would consecrate to him strips of white cloth, tying them to sacrificial trees. The good Es is opposed by the evil female deity

Khosedam

. She is Es’ wife, cast out from heaven by her husband. She lives in the north, underground, and all rivers flow down to her. She is the bringer of evil, misfortune and disease to people and animals.

The heavenly bodies were also personified. The sun was female, the moon male. Various manifestations of natural elements, such as thunder and wind, also appeared as animistic images.

Many beliefs and rituals were based on totemism. The Kets thought that animals were capable of understanding the human language. It was forbidden to speak ill of an animal. It was also believed that animals could pass some of their qualities on to humans. The animals could be reborn, so duck heads were thrown into the water, animal bones piled in the forest. The Bear Cult was widespread among the Kets.

The main object of worship for the family and the clan was the fire. Until the beginning of the 20th century, the fire had been revered as a guardian spirit and a symbol of familial unity. Almost until the 1990s there had been a ban among the Kets against giving matches to strangers. The fire was considered a female spirit. It was fed by pieces of bread, sugar, meat, fat and broth thrown or poured into it. It was forbidden to throw trash or “unclean” objects into the fire. The Kets endowed the fire with the ability to predict the outcome of hunting or fishing.

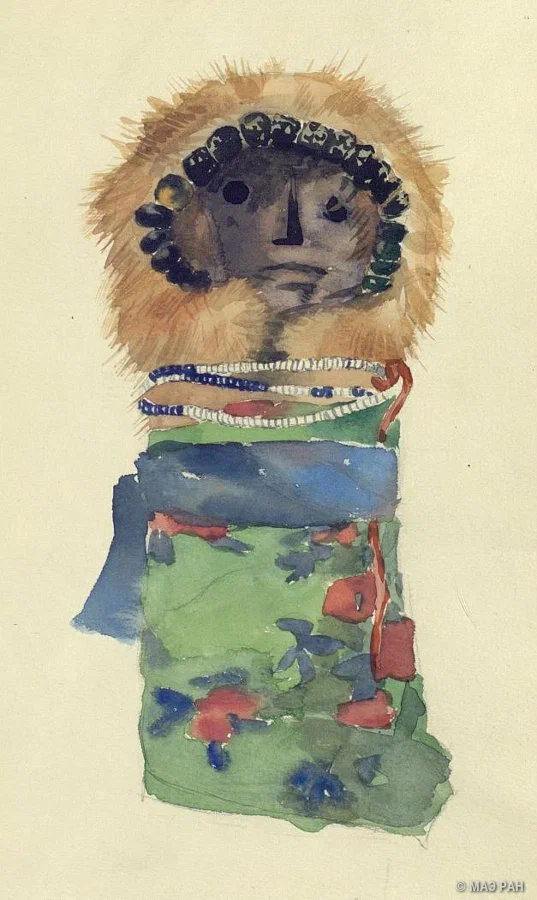

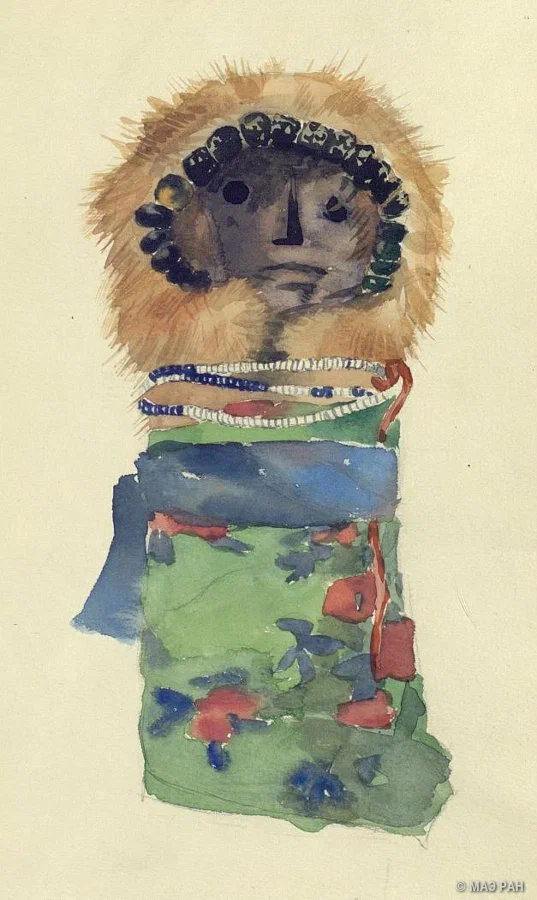

The family guardians were the

alel(s)

, the anthropomorphic dolls believed to “hold” the souls of living women and “release” them after death. Those beliefs co-existed with shamanism, and the shaman would often use these figurines in the rituals. The alel were inherited in the male line.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Orthodoxy peacefully coexisted with pagan beliefs among the people of the older generation, and many considered themselves adherents of both religions. Among the young people, shamanism has been losing ground to Orthodoxy (Krivonogov 2003: 96).

The Kets are trying to preserve what remains of the celebrations and rituals of their ancestors. In 2005, in the village of Kellog, an ancient celebration of River Day was revived. Exhausted by long winter and the mud season characterized by food shortage, people were impatiently waiting for the ice drift, which signaled fishing season.

It was believed that if you pleaded with the river and gave it some food and gifts, it would wake up sooner. Bread, tobacco, and gunpowder were thrown into the water. Today the holiday is held in June and begins with a greeting ceremony to the small river Yeloguy, which is the village’s sustenance-bringer. The celebration is held annually and is accompanied by dugout boat races.

Image of an

alel

home protector. The Kets. Russia, The Krasnoyarsk Territory, Turukhansky district, the village of Kellog. 1960.