Spiritual culture

The worldview of the Kamchadals was based on a combination of Christianity and the customs, rituals, and ideas adopted from the aboriginal population. Of decisive importance was the Russian Orthodox Church with its rituals regulating the main stages of a person’s life path and structuring the annual and daily activities of the congregation.

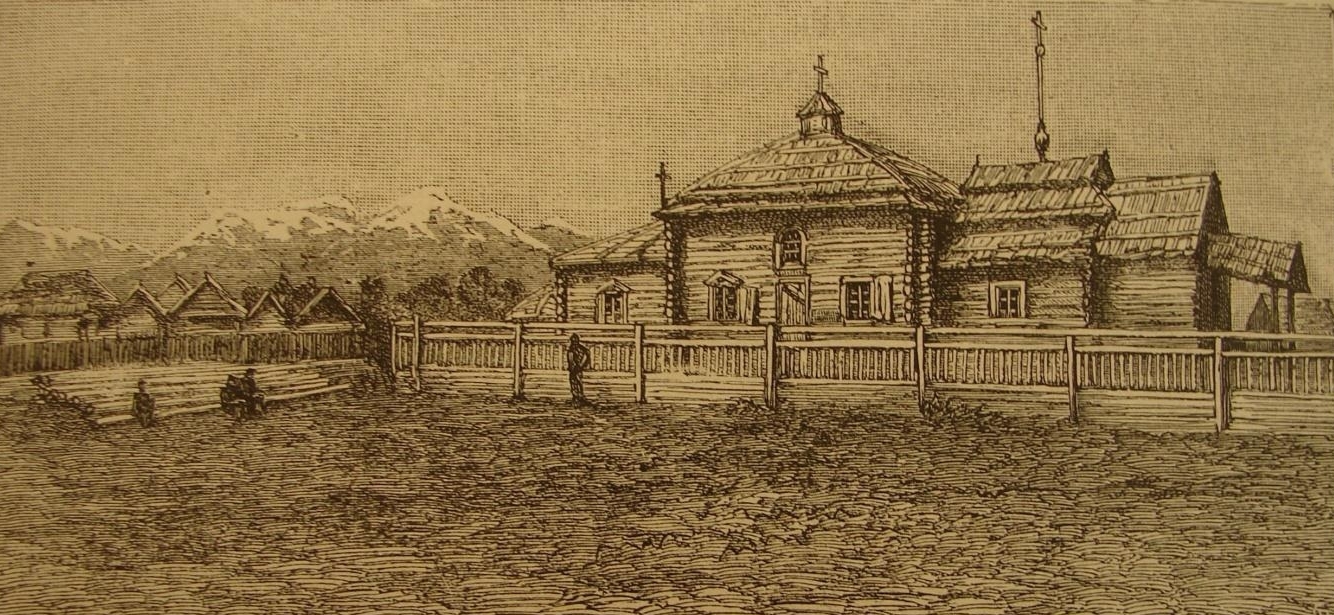

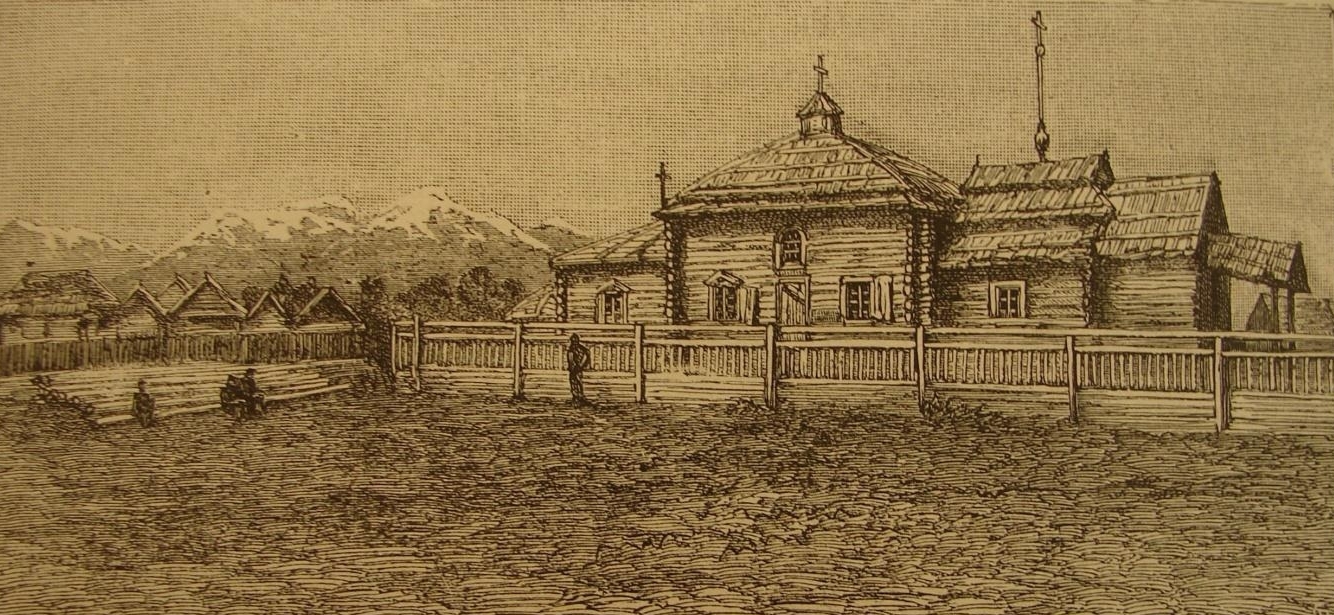

In the first half of the 18th century, there were few churches in Kamchatka. In the second half of the century, there were seven churches, all built in the main Russian settlements. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were 4 Orthodox churches and 8 chapels in the Okhotsk-Kolyma region. Calendar holidays and life cycle rituals largely coincided with the symbolic collective behavior of the Russian rural population. The main work cycles coincided with Orthodox holidays. The summer Akulina Buckwheat Day transformed into Akulina Pink Salmon Day, as it was believed that on this day the intensive fish run began. Kirik and Ulita Day heralded the beginning of the chum salmon run. The most revered autumn holiday of the Intercession signified the start of fur animal hunting and livestock was moved indoors.

The Kamchadals' commitment to Christianity manifested in the first years of Soviet power, when, on their initiative, they created associations of Orthodox believers, supported a priest at their own expense, and often performed basic Christian rituals independently. However, despite their Orthodox persuasion, the Kamchadals also retained some pre-Christian beliefs, introduced by Russian settlers and adopted by the residents. They were ancient demonological beliefs in ghosts (chudinka), prophetic dreams, and omens. Like representatives of other ethnic groups, the Kamchadals believed in spirits, were afraid of “shamanic” places, and avoided them. They often turned to shamans for help.

In everyday life, the Kamchadals shared several aboriginal beliefs, rituals, customs, and folklore. They imagined the world around them as inhabited by the master-spirits of places, to whom it was necessary to make offerings. To explain some natural phenomena, the Kamchadals used the elements of the etiological Itelmen myths about the Raven Kutkh.

The wedding rituals in the pre-Soviet and the first Soviet years displayed some features of the Russian Orthodox ritual. Its usual elements were matchmaking, betrothment (engagement), bride show, church weddings, home celebrations, and visiting. The funeral rite was also basically Orthodox while maintaining several animistic traits. There are ancient cemeteries near many Kamchadal settlements.

In everyday rituals, the Kamchadals mainly adhered to the traditions of the Russian peasantry. The ancient New Year's custom of dressing up was preserved, accompanied by caroling. The mummers played balalaikas and danced. Both the dressed-up carolers and the ceremony itself were called the Selyukiny. An important ritual component was fortune-telling, usually performed at Christmas time. During winter, the favorite pastime of both adults and children was ice slides. At this time, villagers often held evening parties with Russian songs and dances. People would gather in the most spacious house and throw a potluck-style tea party together. The musical instruments were a three-string balalaika and a guitar. The repertoire consisted of Russian round dance, dance, choral, and lyrical solo songs. There was also special Kamchadal folklore: ancient epics and songs.

The socio-economic transformations of the 20th century led to an almost complete loss of folklore and the Kamchadal dialect, which were first relegated to the passive knowledge of the older generation, and then disappeared altogether.

The modern oral folk art of the Kamchadals consists mainly of poems, songs, and ditties dedicated to their native land.

The Kamchadals also highly value the art of rhyming jokes, sometimes quite risqué, similar to the Russian dirty ditties. These poems describe funny incidents during fishing and hunting, where the prey deceives the hunter in the same way as it happens in the fairy tales about Kutkh. The master of this genre was the famous Kamchadal writer and poet Georgy Porotov.

The modern ethnic culture of the Kamchadals is determined by two interrelated processes: the urbanization of the population and the general standardization of life. Recently, the society, along with the rebirth of Orthodoxy, has been experiencing an intensive process of revival of the ancient pagan elements of the Kamchadal culture. Based on local traditions, literature and the culture of the modern Itelmens, ritual calendar holidays are reappearing: the spring holiday of the First Fish, and the autumn holiday “Alkhalalalai”. Many indigenous Kamchatka dwellers of mixed ethnic origin participate in the revived holidays, including the dance marathon.