|

|

Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences

Ekaterina Gruzdeva, Daria Zhornikr

|

Sakhalin-Nivkh Language

I. Sociolinguistic Data

Language Name

The name Nivkh comes from the Amur ethnonym, which means “man”. In Sakhalin-Nivkh this word is pronounced as nigvng, plural nigvngun. A more complete version includes the possessive pronoun of the 1st person plural: min + nigvngun “our people.” In folklore texts, the protagonist is usually introduced as min+ngafk “our comrade,” or “one of us/ours.” The contemporary Nivkh call their language nigvng+dugs “the Nivkh word.”

An alternative name for the language is Gilyak. It had been used in Russian literature until the middle of the 20th century. The Nivkh were called Gilyaks mainly by their Tungus-speaking neighbors (Negidal gilakha, Oroch, Ulch, Nanai gilemi, Orok gile, or gilehe). The documents make it possible to assume that the exonym gilyak entered the Russian language through Even, in which the Nivkh are called gileke, although the form of this word is not entirely typical for the Manchu-Tungus languages.

The meaning of the root *gile is usually associated with the obsolete Ulchi word gile, “large rowboat”, and the Nanai gila “large many-oared boat for six pairs of rowers” (Shternberg 1933: 543, Tsintsius 1977: 152). Thus, the word gilyaks can be translated as “people who travel on boats”. The Nivkh themselves did not call themselves Gilyaks, and this exoethnonym remained alien to the Nivkh throughout the entire period of its use. More information about the Nivkh ethnonymy is presented in the article by Gruzdeva (2021).

Until recently, the Sakhalin-Nivkh language was considered a dialect of Nivkh, but lexical and phonetic differences (albeit with relative proximity at other levels), as well as a lack of mutual understanding with the Amur dialects, made it possible to regard the Sakhalin dialect group as a separate language.

2. General Characteristics

2.1. Number of Native Speakers and the Corresponding Ethnic Group

198 people speaking both Nivkh languages. Source: census of 2010. Number of speakers in native settlements according to the census of 2010: 54 people. Number of people: 4.652 total, 2.149 in the Khabarovsk Territory, 2.290 in the Sakhalin region.

Total number of the Nivkh (census of 2020): 3.863 people.

The number of native speakers of the language (census of 2020) is 117 people.

Currently, the number of fluent native speakers of the language is believed to be about 30 people. Several dozen more speak the language partially or can understand it.

2.2. Age of Speakers

As a rule, only representatives of the older generation can speak the language.

2.3. General Characteristics

The Nivkh language does not have an official status but is considered a language of a small-numbered people. The turning point in the language situation came in the 1950s-60s, with the introduction of the boarding school system. Consolidation of settlements and resettlement of people from small native villages began at the same time.

The percentage of speakers of the Amur Nivkh and Sakhalin-Nivkh languages is as follows: 1897 – 100%; 1926 – 99.5%; 1959 – 77.1% (most speakers bilingual); 1979 – 37.4% (97.3% speak Russian as their native language); 1989 – 23.3%; 2002 – 9.2%; 2010 – 4.5%; 2020 – 1%.

The attitude towards the language is generally positive. The ethnic community desires to preserve the language.

2.3.2. Vitality Status

Throughout the entire area of residence of the Nivkh, the Sakhalin-Nivkh language has the status of “endangered” and is classified as a disappearing language due to a lack of regular communication.

2.2.3. Use in Various Fields

|

Area

|

Use

|

Comments

|

|

Family and everyday communication

|

Yes

|

Minimally, among the members of the older generation

|

|

Education: kindergartens

|

subject (elective)

|

In the Sakhalin region, classes in Nivkh are conducted in kindergartens in Nogliki.

|

|

Education: school

|

means of communication/subject

|

An elective subject in the school of Nogliki. Previously taught in the village of Chir-Unvd, Tymovsky district

|

|

Higher education

|

means of communication/subject (elective)

|

Taught at the Institute of the Peoples of the North in St. Petersburg

|

|

Education: language courses/clubs

|

means of communication/subject (elective)

|

Self-studying language groups in Nogliki

|

|

Media: press (including online publications)

|

No

|

|

|

Media: radio

|

No

|

|

|

Media: TV

|

No

|

|

|

Culture, (including existing folklore)

|

Yes/No

|

Used to a minimal extent in performances of folklore ensembles. The Nivkh folk ensemble “Kekh” (“Seagull”) was formed in 1982 in the village of Chir-Unvd, Tymovsky district, and the national Nivkh ensemble “Ari la mif” (“Land of the North Wind”) was created in 1993 at the District House of Culture of Nogliki.

|

|

Literature in the language

|

Yes/No

|

Vladimir Sangi writes in Sakhalin Nivkh

|

|

Religion (use in religious practices)

|

No

|

|

|

Legislation + Administrative activities + Courts

|

No

|

|

|

Agriculture (including hunting, gathering, reindeer herding, etc.)

|

Yes

|

The Nivkh remember quite well the vocabulary associated with traditional activities (fishing and gathering).

|

|

Internet (communication/sites in the language, non-media)

|

Yes/No

|

In the spring of 2020, WhatsApp and Telegram groups were created for studying Sakhalin Nivkh. The group “Pri Nivkhakh Vavilon” (VKontakte) discusses news and information related to the Nivkh language.

|

2.4. Information on the Writing System

The first alphabet of the language was created in the late 1970s. Vladimir Sangi developed the alphabet based on of which he and Galina Otaina compiled a primer. Subsequently, the alphabet was reformed several times, but its core has remained unchanged. The main objective was to bring the spelling of Nivkh closer to Russian. Over the years, reading materials and other educational aids have been published using the alphabet. The current alphabet of the language has 46 letters, some of which are used only to spell the words borrowed from Russian.

2. Geographical Characteristics

Total Number of Traditional Native Settlements

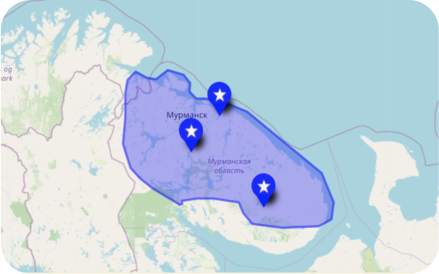

The section lists the names of settlements, indicating in brackets the estimated number of native speakers. The Sakhalin Nivkh live mainly in two settlements: Nogliki (Eastern Sakhalin dialect, 8) and Chir-Unvd of the Tymovsky district (Central Sakhalin dialect, 4), as well as in smaller settlements on the western and eastern coasts of Sakhalin (the number of native speakers is unknown), such as Moskalvo, Rybnoye, Lupolovo, Viakhtu, Trambaus, Val, Katangli, Rybobaza. The Nivkh urban diasporas were formed on Sakhalin in Aleksandrovsk-Sakhalinsky, Poronaysk (Eastern Sakhalin dialect, 2), and Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk (Eastern Sakhalin dialect, 1).

3. Historical Dynamics

The number of native speakers and the size of the corresponding ethnic group according to various censuses (since 1897) and other sources.

|

Year of census

|

Number of native speakers, persons

|

Size of the ethnic group, persons

|

|

1897

|

6.194

|

—

|

|

1926

|

4.130

|

4.076

|

|

1939

|

|

3.857

|

|

1959

|

2.823

|

3.700

|

|

1970

|

2.188

|

4.420

|

|

1979

|

1.696

|

4.397

|

|

1989

|

1.215

|

4.673

|

|

2002

|

688

|

5.162

|

|

2010

|

198

|

4.652

|

|

2020

|

117

(Sakhalin Nivkh language)

|

3.863

(all Nivkh)

|

II. Linguistic Data

1. Position in the Genealogy of World Languages

Sakhalin Nivkh and Amur Nivkh are closely related and form the Amuric (Nivkh) language family. They used to be regarded as a single isolated Nivkh language, which (according to the classification of Leopold Shrenk) was included in the group of Paleo-Asian languages.

2. Dialects

The Sakhalin Nivkh language, spoken in northern Sakhalin, has several local variants that represent a dialectal continuum. Historically, the Nivkh lived in small villages along spawning streams and the sea coast. On Sakhalin, the settlements were more homogeneous in composition, each usually including one clan.

The most conservative dialects are the extinct South Sakhalin dialect, spoken by a small group of the Nivkh in the Bay of Terpeniya, and the Central Sakhalin dialect, spoken on the west-central coast of Sakhalin and in the Tym River basin. The more innovative East Sakhalin dialect is used on the northeast coast of the island.

3. Brief History of Academic Research of the Language

The first reliable information about the material and spiritual culture of the Nivkh appeared at the end of the 19th century, when Wilhelm Grube published the data collected by von Schrenck and von Glen during their expedition to the Amur region, organized by the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences in 1854-56. An extensive corpus of Sakhalin-Nivkh folklore was recorded at the end of the 19th century by two political deportees, Lev Shternberg and Bronislav Pilsudski. Some of the materials were published in 1900 and 1908.

Subsequently, linguistic studies of Sakhalin Nivkh were continued in different parts of the world. Various topics of Nivkh phonology and grammar were researched in Russia by Erukhim Kreinovich (1979), Lyudmila Gashilova (1983, 1988, 1981), and Vladimir Rushchakov (1981, 1983, 1989). A Sakhalin Nivkh dictionary, compiled by Lyudmila Gashilova and Vladimir Sangi, was published in 2003

In Japan, the study of Nivkh began with a brief description of the South Sakhalin dialect by Nakanome Akira (1927) and was continued by Masahiro Takahashi, who published a grammar introduction to the dialect (1941), and Takeshi Hattori, who studied, in particular, the Nivkh taboos (1941), terms of kinship (1942), honorific expressions (1943) and published a short grammar essay on the Nivkh (1955). Various aspects of the Nivkh language were discussed in the works of Watanabe (1983, 1992), Nakagawa (1993), and Tangiku.

Among the American scholars, Robert Austerlitz paid special attention to the issues of internal reconstruction in his numerous publications on the South Sakhalin dialect (1980, 1982, 1984, 1990, 1994), while Roman Jacobson (1971) described in detail the consonant alternation system.

In recent decades, active work on describing various aspects of the Nivkh language has been carried out by Ekaterina Gruzdeva, including in collaboration with Juha Janhunen.

4. General Linguistic Information

The richest layers of vocabulary are those describing fishing and hunting forest animals, as well as natural phenomena, and spatial and kinship-related terminology. These layers are endemic and contain the least number of borrowed words. The vocabulary associated with new types of economic activity and cultural life mainly consists of Russian borrowings. In the modern language, however, borrowings are not accepted. The Amur dialect also contains a large layer of vocabulary borrowed from the Manchu-Tungus languages. Traditional names are often used as surnames. Toponyms are generally preserved, but often in a Russified form.

Nivkh is often cited as a typologically exceptional or even unique language. It differs in many ways from the other languages spoken in the Amur region and Sakhalin, most of which belong to the Manchu-Tungus group.

The language has an exceptionally developed and compact system of consonantism, in which the phonemes are maximally opposed via five places and seven manners of articulation. Such richness is mainly associated with the developed system of noise consonants (obstruents), which can be compared only with the system of obstruents in Korean.

Among the noise consonants, a group of postvelar consonants stands out, including three stops and two fricative phonemes. In this regard, the closest parallels are found only in the Manchu language with its three postvelar consonants. The Nivkh language also has a typologically rare group of liquids, which includes not only the dental lateral “l” and the postalveolar trill “r”, but also the voiceless trill “r̥”.

The Nivkh language is known for its mechanism of morphological alternations, which can be considered unique not only geographically, but also in general typological terms. Alternations play a significant role both in phonology and syntax since their presence or absence often serves as the only indicator of a particular syntactic function. Among the languages of Eurasia, a similar phenomenon is observed only in Celtic languages.

The prefixation, which is characteristic of some Nivkh nominal and verbal forms, is not found in the neighboring Altaic languages, but it is recorded in the Ainu language, with which Nivkh came into contact on Sakhalin.

Another feature that distinguishes Nivkh from its immediate neighbors is its qualitative verbs, which are also widespread in the languages of the Pacific region, Korean and Japanese.

Demonstratives, vocabulary related to spatial orientation, and numerical classifiers are present to varying degrees in most languages geographically close to Nivkh, but only Nivkh demonstrates exceptionally developed systems in each of these areas.