Kumandin Language

I. Sociolinguistic Data

1. Existing Alternative Names

Kumandins (based on the name of one of the ethnic groups; etymologically, this ethnonym is compared to куман and linked with the Turkic root qu: <*qub ‘pale’ + -man).

There are several variants of this self-designation: куванды, куванта, кувандык, as well as тадар кижи. Sometimes, Kumandins are divided into Örö Kumandins, or Upper Kumandins inhabiting the upper course of the Biya River, and Altyna Kumandins, or Lower Kumandins living in the middle course of the Biya River. As an ethnic group, Kumandins developed as a result of long-term contacts between the ancient Samoyedic, Ugrian, and Yeniseian populations and the Turkic groups that arrived on this territory later.

In the Soviet period, Kumandin was considered a dialect of the Altai language. In 2000, Kumandins were included in the list of indigenous small-numbered peoples of the Russian Federation, and their language was recognized as a separate language (by RF government decree № 255 of March 24, 2000).

2. General Characteristics

2.1. Number of Native Speakers and the Corresponding Ethnic Group

Number of native speakers: 738 people. Source: 2010 Census.

Number of speakers in traditional settlements based on the 2010 Census: 240 people. Source: 2010 Census.

Population (based on the 2010 Census): 2,892 people. .

Urban population speaking Kumandin appears to be overestimated.

>

2.2. Sociolinguistic Characteristics

The language use is currently limited to older generation. Based on the sociolinguistic research of recent years, the middle-aged generation, with very few exceptions, comprises only passive speakers. Members of the younger generation do not speak Kumandin or encounter it in their everyday life, even though they might attend Kumandin language courses.

As I. Nazarov, ethnographer, and candidate of historical studies asserted, “At the turn of the century, there were still old people speaking Kumandin, which allowed them to record an extensive terminology with regard to housekeeping, as well as material and spiritual culture.”

N. Urtegeshev, linguist, PhD in philology, argued, “In the course of our 2003 expedition, our survey covered 80% of the Kumandin population of the Soltonsky district, Altai Krai (232 people of all ages). 49.5% of respondents indicated Kumandin as their native language. There were no children between 8 and 12 that considered Kumandin to be their mother tongue – 0%. 21.5% of respondents considered Russian to be their native language. 29% of them considered both Russian and Kumandin to be their mother tongues. To determine the level of proficiency in Kumandin, the respondents were asked how well did they think they knew their language. 30.3% of respondents answered that they were fluent; 12.7% could speak Kumandin but not without making mistakes; 13.5% understood but did not speak; 6.8% got the gist; 16.5% understood some words and everyday phrases; 20.2% of the population did not know the language. Thus, about 79.8% of respondents speak Kumandin to some extent, whereas 78.5% believe that their native language is either Kumandin or Kumandin along together Russian”.

Threat of Extinction

2B: The language transmission between generations has been virtually interrupted, and despite many efforts to revitalize it, the younger generation still does not perceive Kumandin as its mother tongue. There is still everyday communication in Kumandin, although it is mostly confined to set forms: songs, fairy tales, religious and ceremonial texts. Language activists of the older generation are doing their best to slow down and reverse the process of language loss, but there are basically no active language speakers in the younger generation.

2.4. Information on the Writing System

In the middle of the 19th century, the missionaries of the Altai Spiritual Mission elaborated a system of writing for Altaic languages. In the pre-revolution period, Kumandins used it to record their own language. The first texts in Kumandin appeared in the second half of the 19th century during the spread of Christianity in Altai resulting from missionary activities. These texts were religious by nature, among others, translations of some fragments of the Holy Scripture.

In the early 1930s, an attempt was made to teach Kumandins in their own language. In order to achieve this goal, a Latin-based Kumandin alphabet was created in 1933, edited by N. Kalanakov and K. Filatov. Then the teaching in Kumandin stopped.

Since Kumandin was recognized as a language in its own right in the 21st century, there began a new campaign to bring the language back to schools. In 2005, there was published a Cyrillic-based ABC named Азбука кумандан [ABC for Kumandin People] by L. Tukmachev. The Kumandin alphabet was based on the graphic tradition of the literary Altaic language using the Russian version of Cyrillic. It adequately reflects the Kumandin phonological system, while at the same time remaining as close as possible to the alphabet of the Altaic literary language. It facilitates the task of learning the Kumandin system of writing for the children living in the Altai Republic and studying Kumandin. The Kumandin alphabet suggested by Tukmachev consists of 38 letters (the Altai alphabet totals 37). Taking into account the peculiarities of Kumandin, Tukmachev added to the Altai alphabet the graphemes Ғғ and Њњ, but excluded j. A somewhat different Kumandin ABC was suggested by M. Petrushova. Her alphabet includes 41 symbols — she added the letters Ққ, ɣ, and Ћћ. Symbols Ққ and Ғг are used to designate uvular versions of the phoneme [k]: letter Ққ for the voiceless variant (at the beginning or the end of the word, and when combined with voiceless consonants), letter Ғг for the voiced variant (when combined with vowels or sonorants). Grapheme ɣ is used to convey a specific North Altai sound that is only used at the end of a word or a syllable (in the Tukmachev alphabet, this sound is indicated with the symbol Ғғ). Letter Ћћ conveys a mediolingual noise consonant that occurs very often in Kumandin parlance at the beginning of words (the Altai alphabet indicates a similar occlusive sound with the grapheme Jj, but these sounds are somewhat different).

The Kumandin alphabet is based on a mix of phonetic and phonemic orthography, which is necessary to avoid misrepresenting the specifics of the pronunciation of this language.

Modern Kumandin alphabet (L. Tukmachiov’s version)

|

А а

|

Б б

|

В в

|

Г г

|

гғ

|

Д д

|

Е е

|

Ё ё

|

|

Ж ж

|

З з

|

И и

|

Й й

|

К к

|

Л л

|

М м

|

Н н

|

|

Ҥ ҥ

|

Нь нь

|

О о

|

Ö ö

|

П п

|

Р р

|

С с

|

Т т

|

|

У у

|

Ӱ ӱ

|

Ф ф

|

Х х

|

Ц ц

|

Ч ч

|

Ш ш

|

Щ щ

|

|

Ъ ъ

|

Ы ы

|

Ь ь

|

Э э

|

Юю

|

Я я

|

|

|

3. Geographic Characteristics

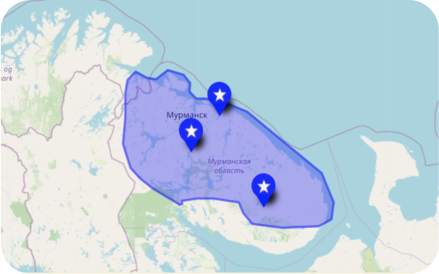

3.1. Constituent Entities of the Russian Federation with Ethnic Communities

Altai, Altai Territory, Kemerovo Region.

3.2. Total Number of Traditional Native Settlements

Around 10.

Kumandins live in small groups in the Turochaksky District of the Altai Republic, Krasnogorsky and, Soltonsky Districts of the Altai Krai, and Tashtagolsky District of the Kemerovo Region. More than half of Kumandins live in the cities: of Biysk, Gorno-Altaysk, and Tashtagol.

At present, most of the localities where Kumandins traditionally lived and predominated have either disappeared or are on the verge of closing down. Within the localities traditionally inhabited by native speakers, Kumandins are concentrated in the following settlements: Krasnogorskoye, Yegona, Pil’no, Kaltash, Uzhlep (Krasnogorsky District), Solton, Shatobal, Suzop, Nizhnyaya Neninka (Soltonsky District), Sankin Ail and Shunorak (Turochaksky District). Based on the 2010 Census, there were 40 Kumandins in the countryside of Kemerovo Region.

4. Historical Dynamics

The number of native speakers and corresponding ethnic group based on various censuses (starting from 1897) and other sources.

|

Census Year

|

Number of Native Speakers (men)

|

Size of Ethnic Group (men)

|

Comments

|

|

1897

|

-

|

4,092

|

|

|

1926

|

2,908

|

6,334

|

|

|

1937

|

-

|

-

|

Up until 2002, Kumandins were considered as Altai people

|

|

1939

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

1959

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

1970

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

1979

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

1989

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

2002

|

1,044

|

3,114

|

|

|

2010

|

738

|

2,892

|

|

II. Linguistic Data

1. Position in Genealogy of World Languages

Altai macrofamily > Turkic family > Central-Eastern group > (Gorno) Altai group > North Altai subgroup.

2. Dialects

Kumandin has no dialects. Researchers distinguish Turochaksky, Soltonsky, and Krasnogorsky (Starobardinsky) local parlances. They have some differences in pronunciation, vocabulary, and morphology, but nobody ever undertook any comprehensive study of them.

3. Brief History of Language Study

The first texts in Kumandin appeared in the second half of the 19th century during the spread of Christianity in Altai resulting from missionary activities. These texts were religious by nature, among others, translations of some fragments of the Holy Scripture.

The first recordings of Altai folklore were carried out by a distinguished German Turkologist Vassily Radlov (Wilhelm Radloff) in 1860, 1861, 1865—1967, and 1870. Several Kumandin texts were published in the first volume of his Образцы народной литературы тюркских племен [Samples of Folk Literature of the Turkic Tribes].

In the 1940s—1950s, Nikolay Baskakov (1905-1996), a distinguished philologist and Turkologist, collected linguistic and folklore materials in Altai, where he used to live during World War II at the time of evacuation of the Moscow Pedagogical Institute. The researcher showed the differences between Altai dialects in his multi-volume publication: the first volume featured the dialect of “Black Tatars” (Tuba Kizhi), the second one, the Kumandin dialect (Kumandin Kizhi), the third one, the dialect of “Lebedinsky Tatars” (Chelkans). Each volume offers a systematic description of the dialect comprising a grammatical profile, a series of texts with Russian translations, and a dictionary. These volumes contain the recordings made by both the researcher himself and philology students of the Gorno-Altaisk Pedagogical Institute (nowadays, the State University) in northern Altai districts: Mayminsky, Choysky, Turochaksky. So far, Baskakov’s publication remains the most comprehensive description of Kumandin.

On the whole, Kumandin did not attract any special attention from linguists. There were only 2 small Kumandin-related publications by N. Dyrenkova, a famous linguist and Turkologist of the middle of the 20th century, but even they were not about language, but folklore.

In the second half of the 20th century, folklore materials were collected by the employees of the Gorno-Altaisk Research Institute of Language, History, and Literature created in 1952 (at present, the Institute of Altai Studies named after S. Surazakov of the Altai Republic). It launched a project of targeted collection of materials of all folklore genres with large-scale expeditions. In addition to the recordings made during these expeditions, the collection of fairy tales from the Institute’s archives was replenished with the materials sent by amateur collectors. A considerable contribution to the collection of the Kumandin folklore was made by ethnographer F. Satlayev (1921—1995). Unfortunately, these materials are only available to researchers, since they were never systematically published and digitized. Some samples of Kumandin texts from this collection were also included in the Altai volumes of Памятники фольклора народов Сибири и Дальнего Востока [Monuments of Folklore of the Peoples of Siberia and Far North]: Алтайские народные сказки [Altai Folk Tales], volume 21, and Несказочная проза алтайцев [Altai Nonfictional Prose], volume 30.

There are more ethnographic than linguistic studies of Kumandin. The Biysky Local History Museum features a very extensive museum collection and an exposition dedicated to Kumandins. Boris Kadikov was crucial to its creation and now his work is carried on by Ivan Nazarov.

When it comes to research papers in linguistics, it is impossible not to mention 2 monographs by I. Selyutina on the Kumandin phonetics (Кумандинский консонантизм: Экспериментально-фонетическое исследование [Kumandin Consonantism: Experimental Phonetic Research]. Novosibirsk, 1976; Кумандинский вокализм: Экспериментально-фонетическое исследование [Kumandin Vocalism: Experimental Phonetic Research]. Novosibirsk, 1998). We have no knowledge of any other Kumandin-related linguistic research.

4. The Most Prominent Linguistic Characteristics from Typological and Areal Perspective

There were no extensive studies of Kumandin, so it is hardly surprising that the researchers have yet to find unique features that would distinguish it from other Turkic languages of Siberia. Perhaps the most striking peculiarity is the contraction of auxiliary verbs in frequently used analytical constructions that are much more widely used in Kumandin than in neighboring languages. For instance, the past tense form that ends in -ган usually implies the contraction of the auxiliary verbs йис [send], сал [put], designating the completion of an action, and бер [give], designating the completion of an action for another person:

кыс агасына письми ший ал келип ийебен (< ийе берген)

[a girl wrote a letter to her father]

аҥзонда тыҥдан, тыҥдан тапинзан (< таппин салган)

[then he looked for her, he looked, but couldn’t find]

кӱнза кӧрзӧ кӱн ач парыгин (< парып ийген)

[we looked at the sun, but it was already down]

мен апырсам (< алып парып салганым) [I accompanied]