|

|

Institute of Linguistic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences

M. Yu. Pupynina

|

The Kerek Language

The sociolinguistic situation

1)

General characteristic

s

Kerek is an extinct (“dormant”) Chukotko-Kamchatkan language. Currently, there are no people who can produce a coherent text in Kerek, although descendants of its speakers calling themselves Kereks are still living. It is possible that there are still the so-called “semi-speakers” of Kerek who can recall a few words in the language and understand a few simple sentences in Kerek, but there is no conclusive proof that such people do exist.

Until the end of its existence, Kerek was used purely at homes and apparently only by the elderly people who knew the language. In the 1930s, ethnographers and linguists first began studying Kereks and their idiom, and in the 1950s, Kerek was “raised ” from the continuum of Koryak dialects to the status of a language. Its critical status became immediately apparent, yet there is very little sociolinguistic and historical linguistic information in published research on the circumstances of Kerek’s existence. In the 1970s, Kerek names were still being used (for instance, elderly Kerek speakers still had “at-home” Kerek names) and there were storytellers who could tell ancient Kerek “proto-epic” legends. Of the four informants who were the sources of biographic and folklore texts in Kerek, the youngest one, Ekaterina Khatkana was at the time about 50. There had been other Kerek speakers, but no work was done on recording texts in Kerek from them. By the 1990s, the language had fallen out of use nearly completely, although three persons, all elderly, still remembered the language and sometimes used it. In 2005, the only living speaker of Kerek, Ekaterina Khatkana, died aged 82.

Both indirect historical information and ethnographic evidence indicate that once-numerous Kereks had been assimilated by the Chukchi and, to a lesser degree, by Koryaks before the arrival of the Soviet system. After the founding of the USSR, the last Kereks speaking their language turned out to be living in the Chukotka Autonomous Area, an administrative unit dominated by the Chukchi culture and language tradition that was being gradually pushed out by the Soviet Russian-language tradition.

No writing system had ever been designed for Kerek. Kereks themselves apparently viewed the status of their people and language with some modesty claiming that “every fourth word in their language is Kerek proper, and all other words are Chukchi and Koryak” [Leontiev 1983: 67].

The Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages are divided into two branches, Chukchi-Koryak and Itelmen. The Chukchi-Koryak branch includes only two groups, the Chukchi group and the Koryak group. The Chukchi group comprises only the “monolithic” Chukchi language. Most linguists who are well-versed in the matter believe that Kerek is closer to the Koryak group of the Chukchi-Koryak branch of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages. Defining with greater precision the place of Kerek on the genetic tree of Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages requires studying all available materials on Kerek. Such studies are very difficult to conduct since most materials on Kerek still remain unpublished, and publishing them requires doing the monumental work of designing a writing system for Kerek and unifying information collected by different researchers.

2)

Geographic

distribution

:

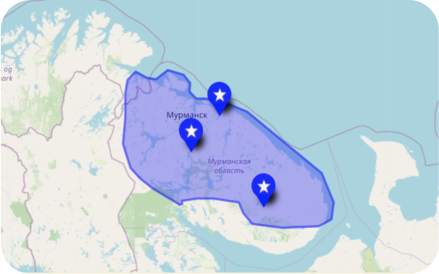

Previously, Kereks were settled along the southern coast of the Anadyrsky Liman all the way to the Anastasia Bay. Since their occupations involved only short-distance seasonal migrations, they, on the one hand, did not have permanent settlements on the coast and, on the other hand, never traveled further than several dozen kilometers away from the coastline.

With respect to Russia’s administrative units, Kereks’ traditional lands were on the border of the Chukotka Autonomous Area and the Kamchatka Territory (previously the Koryak Autonomous Area). In the Soviet era, Kereks in Chukotka were recorded as living in the villages of Khatyrka and Meinypilgino. In the 1990s, the Kerek language was still sometimes used in the village of Meinypilgino in the Beringovsky District of the Chukotka Autonomous Area. The last villager fluent in Kerek, Ekaterina Khatkana, died in 2005.

The 2020-21 Census recorded three Kereks, two women and one men, in the Chukotka Autonomous Area (Census 2020—2021). None of the them lives in the villages where Kereks were recorded in the 20th century; one Kerek, however, is recorded in the city of Anadyr, the capital of the region, and one of the women is recorded in the village of Vayegi in the south of Chukotka, close to Kereks’ original settlement area. Kereks’ descendants presumably still live in Chukotka’s southern villages: Khatyrka, Meinypilgino, the city of Beringovsky that is the district center, and possibly in the village of Vayegi and in the city of Anadyr that is the capital of the Chukotka Autonomous Area. Some traces of Kerek influence may be sought in the north of Kamchatka.

3)

Historical

dynamics

:

Historical works first mention Kereks only in the late 19th century. The term “

Kereks

” comes from the Chukchi language: the Chukchi called them

kereki-t

(sg.

kerek

). Vladilen Leontiev writes that Kereks’ endonym is “coastal [people],”

an’k’alakku

. Previously, Kereks were mentioned as Koryaks or the Chukchi, although some explorers, including members of Vitus Bering’s crew, noted a special group of people with a lifestyle that was not typical for those lands (with a diet comprised of almost equal shares of marine animals, fish, and fowl) and with a language similar to both Chukchi and Koryak. Living on a large territory stretching from the Anadyrsky Liman in the north to Cape Olyutor in the south, Kereks constituted a fairly large and fairly detached group until the time of Chukchi-Koryak wars when Kereks found themselves sort of “in the middle.” Economic decline resulted in Kereks increasingly going to work for the Chukchi as shepherds and so gradually coming to lose their language and culture.

The 1897 Census recorded about 600 Kereks, while Vladimir Bogoraz who conducted a census in the northeast of Russia in 1901 recorded 644 Kereks (see Jochelson 1997: 38), although this figure likely includes several Koryak families. The 1926 Census gives more likely information: 315 Kereks. Nikolay Schnakenburg, based on his field research, believed that in 1937, Kereks numbered 128 persons.

Pyotr Skorik who collected information on Kereks in 1954—1956 commented on the lamentable situation with the Kerek language, “Kerek is on the verge of being entirely extinct. Currently, it is spoken by only a few families totaling about 100 persons” [Skorik 310]. Apparently, the figure of 100 persons can be taken to refer to the overall number of people with some command of Kerek in the 1950s, including those family members who did not speak Kerek well, but still understood it, i.e. this figure included people with both active and passive knowledge of Kerek.

Vladilen Leontiev noted that in 1970, the village of Meinypilgino had about 30 people, members of eight families where some of the elder family members were Kereks. There were no purely Kerek families. Out of those 31 persons, only 15 self-identified as Kereks and only 11 spoke Kerek. By 1975, one five were left. Others “used the Chukchi and Russian languages” (p. 18). In 1975, the situation in the village of Khatyrka was even worse: Leontiev encountered only nine people speaking Kerek while 11 Kereks were recorded living there.

Alexander P. Volodin reported that in 1991, three persons spoke Kerek: Ekaterina Khatkana, Nikolay Etynkeu, and Ivan Uvagyrgyn. In addition to Kerek, they were also fluent in Chukchi and spoke some Russian. In the 2000s, only the youngest of them, Ekaterina Khatkana, was alive. Table 1 shows the Kerek speaker dynamics.

Table 1. The Kerek language speaker dynamics

|

Year

|

Kerek speakers

|

|

1950s

|

100 (active and passive command)

|

|

1970s

|

20 (active command)

|

|

1990s

|

3 (active command)

|

|

2000s

|

1

|

|

2010s

|

0

|