The Northern Khanty Language

General Characteristics

The Number of Native Speakers and the Corresponding Ethnic Group

It has proved to be challenging to estimate the number of speakers of Northern Khanty based on the census data. In all censuses conducted in the Russian Empire, the USSR and Russia, the Khanty have always been fused together and census-takers made no attempt to separate them into ethnographic groups (for example, the northern, the southern and the eastern). Similarly, in the census of 2010, the speakers of Northern Khanty and the speakers of Eastern Khanty were counted together. In 2010, 30.943 people called themselves Khanty, and approximately 11.5 thousand indicated Khanty as their native language. In the census of 2010, in addition to the question about the native language, a question about native language proficiency was added, to which approximately 9.5 thousand Khanty responded “proficient.” According to the All-Russian Population Census of 2020, 31.600 people called themselves Khanty, 5.403 people spoke the Northern Khanty language, and 8.665 people considered it their native tongue.

Age of Speakers

The number of native speakers is relatively small among the younger generations, yet the people of the older generation speak the Khanty language quite well. There are a few reasons for poor language proficiency among the younger generations. First, most children receive their education in boarding schools, and therefore do not see their family for a significant part of the year, having no contact with the older relatives with whom they could communicate and practice. Secondly, traditional occupations are disappearing, which leads to people moving to multinational villages and cities, where it is more difficult to preserve their native language. Finally, there are internal changes in the language itself as it needs to be adapted to modern realities. Still, the preservation and development of Northern Khanty are not impossible, as any language can successfully express both the traditional culture and the newly emerged areas of life.

Sociolinguistic Characteristics

The Khanty language is seriously endangered. The problem is that the transmission of the language from the older to the younger generation has largely ceased. Outside the family, the Russian language is used everywhere (in education system, shops, healthcare organizations, state institutions). This situation is common for many indigenous languages, and special efforts are needed to maintain them. Moreover, the initiative must come from both sides, from the state and from the community itself. In the 21st century, it is important not to preserve the language per se, trying to maintain its connection with the traditional culture year after year, but to develop and support its use in the modern world, in the fields of music, texting, Internet sites, etc. Such projects do exist for Khanty. One important step is the development of a keyboard layout that allows one to communicate on the Internet, text in instant messengers, etc.

Geographical Characteristics

3.1. Constituent entities of the Russian Federation with ethnic communities

Native speakers of the Northern Khanty language live mostly in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Area and the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Area. In all censuses, starting with the first general census of the Russian Empire in 1897, all of the Khanty (who were then called Ostyaks) were counted together, without dividing them into separate ethnographic groups (the northern, the southern and the eastern). Therefore, the speakers of Northern Khanty, Southern Khanty and Eastern Khanty were also grouped together. The total number of Ostyaks, according to this census, was 19,663. It can be assumed that at the end of the 19th century, in the basins of the Northern Sosva and the Lyapin (Sygva), the answer about ethnicity did not always coincide with the native language of the respondent. The reason for that was that during the 19th century, the processes of formation of the northern group of the Mansi were still active in these territories, and the groups of the Northern Khanty lived on these lands, as well. The group of the Northern Mansi was formed largely due to the inclusion of the Khanty who lived in this territory. Therefore, during the census some of those regarding themselves as Ostyaks (the Khanty) actually continued to speak Mansi and not Northern Khanty.

The data from the later censuses also present the Khanty as a single people. According to the censuses of 1959-1989, it is clear that the percentage of native speakers was gradually decreasing: the number of Khanty increased from 19 thousand to 22.5 thousand people due to natural population growth during this period, yet the number of those who indicated Khanty as their native language decreased, albeit slightly, from 14.5 thousand to 14 thousand people According to the All-Russian Population Census of 2020, 31.600 people called themselves Khanty, 5.403 people speak the Northern Khanty language, and 8.665 people consider it to be their native tongue.

Linguistic Data

Despite the fact that the Khanty, occupying vast territories from the Vasyugan in the southeast to the polar territories of the northern Ob, have formed several significantly different cultural entities, many people still refer to them as a single ethnic group. Yet, the ethnographers do distinguish three large communities: the Northern, the Southern, and the Eastern Khanty. At the same time, the cultural differences between the territorial groups of the Khanty are deeper than those existing between them and the neighboring Mansi groups. For example, Vladislav Mogilnikov and Zoya Sokolova (2005) identified significant similarities in the culture of the Northern Khanty and Mansi and significant differences between them and the Eastern Khanty. The situation is mirrored in the Khanty language: under the umbrella term “Khanty” the experts group several dialects so different that they can rightfully claim the status of separate languages.

The three large dialects (many would argue that they should be treated as languages) are usually distinguished as three ethnographic groups: the northern, the southern, and the eastern. To date, primarily the Northern and the Eastern Khanty languages have been preserved. Each of them, in turn, is divided into dialects and sub-dialects. The Northern and the Eastern Khanty are very dissimilar, so the Atlas treats them separately.

Here are the main differences between these languages:

-

In Eastern Khanty there are from fifteen to eleven vowels, while in Northern Khanty there are eight or nine.

-

In Eastern Khanty, vowel harmony has been preserved (that is, all vowels in one word must be either front: i, e, ä, ö, ü, or non-front: i̮, a, o, u, etc.). In Northern Khanty no traces of this have been preserved.

-

In Eastern Khanty the verb has four past tense forms, in Northern Khanty there is only one.

-

Eastern Khanty has about eight cases, while Northern Khanty has but three.

-

In Northern Khanty there are special verb forms that describe an action that the speaker has not witnessed and information about which he has received from some indirect signs (for example, by footprints in the snow) or learned from other people. In Eastern Khanty, such shades of meanings cannot be expressed grammatically.

The closest linguistic relatives of Northern Khanty are, naturally, Southern Eastern Khanty. Together with the Mansi language, they compose the Ob-Ugric language group. The first word points to the main territory of settlement of the Khanty and Mansi, the Ob basin. The second indicates the closest relative of the Mansi and Khanty languages, the Hungarian language from the very heart of Europe (Ugrians is the name of the ancestors of the Hungarians). These three languages (Khanty, Mansi and Hungarian, arranged both in the order of their relative location from east to west, and in the degree of linguistic proximity) constitute the Ugric sub-group of the Finno-Ugric languages. The Finno-Ugric group, along with the Ugric languages, includes such languages as Komi, Udmurt, Finnish, Estonian, Sami, Ingrian, Veps, and Votic.

In turn, the Finno-Ugric and the Samoyed languages form the Uralic family of languages. The Samoyed languages include the languages of Tundra Nenets, Forest Nenets, Enets, Nganasans, and the Selkup. These are the easternmost languages of the Uralic language family.

Figure 1. Peoples of the Ural Region

There is a direct correlation between ethnicity and language. From the linguistic point of view, the map above should be much more detailed. The territory of the Khanty settlement (with no internal borders) is marked in orange along the Ob and Irtysh.

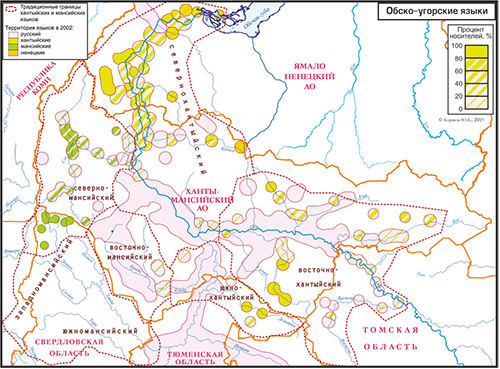

Figure 2. Ob-Ugric Languages

Figure 2 shows the map of the traditional settlement of the Ob-Ugric peoples, which reflects the position of these two languages much more clearly. It shows the percentage of speakers of the following languages in various localities: Khanty, Mansi, Nenets and Russian (note: in this case we are talking about language proficiency, and not about the ethnicity of the people living here).

Northern Khanty and Its Neighboring Languages

The Ural Mountains cut the territory of the Uralic languages into two parts: the Asian (Siberian) and the European. At the same time, in Siberia, only two groups of the Uralic languages are represented: the Samoyed languages and the Ob-Ugric languages. If we approach these two groups only from the point of view of linguistic relationship, it turns out that they are not too close to each other: the Uralic languages split about 5,000 years ago into the Samoyed and the Baltic-Finnish branches. This roughly correlates with the age of the Indo-European language family; so, from a historical point of view, Khanty is as distant from any of the Samoyed languages as Russian is, for example, from Greek, Armenian or Hindi. Still, languages may share some features not only due to common origins, but also because of the contacts among their speakers. In other words, languages may be similar to each other not only like brothers or cousins, but also like old close friends. The prerequisites for contacts are, first of all, the geographical proximity, and secondly, the commonality of the culture of the ethnic groups speaking these languages. As a result, a long parallel development in the same geographical and cultural area makes the languages become similar to each other (starting with lexical borrowings and ending with the mutual similarity of some grammatical features).

The Samoyed languages are the immediate eastern neighbors of the Ob-Ugric languages (at present only of Khanty, but in a more distant era, perhaps also of Mansi). The Ob Ugrians have much in common in the material and spiritual culture with the Samoyed peoples, primarily with the Forest Nenets (native speakers of the Neshchan language), Tundra Nenets and the Selkup. So in the West Siberian region several contact points arose between the Samoyed and Ob-Ugric languages: these are contacts between the Eastern Khanty and the Selkup, between the Eastern Khanty and Forest Nenets, between the Northern Khanty and Forest Nenets, and, finally, between the Northern Khanty, the Northern Mansi and the Tundra Nenets.

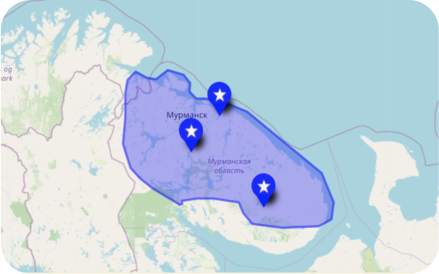

Figure 3. The Neighboring Languages of Northern Khanty

The Internal Dialectical Division of Northern Khanty

Northern Khanty has four large dialects. Geographically, one can trace them going from north to south: Northern (Ust-Sob and Ust-Poluy sub-dialects), Shuryshkar (Pitlyar, Syn and Kunovat sub-dialects), Kazym (Berezovo-Tegin, Ust-Kazym and Upper Kazym sub-dialects), and the Middle Ob dialect, which is currently represented by the Sherkal sub-dialect. The name “Middle Ob” is perhaps not entirely apt, since geographically the middle course of the Ob is considered to be the area from the mouth of the Tom to the mouth of the Irtysh, that is, the territory inhabited by the eastern, not northern Khanty, but in linguistics the term Middle Ob dialects is assigned specifically to the southernmost group of the Northern Khanty dialects.

Figure 4. Northern Khanty Dialects

Brief History of the Academic Research of the Language

The first mention of the Khanty dialects is contained in a handwritten dictionary of the 18th century. During that period, the Russian Academy of Sciences was commissioned to compile comparative dictionaries of the languages of the world. Some of the materials on Khanty were published in the 1780s by Pyotr Simon Pallas.

Hungarian and Finnish scholars have traditionally shown particular interest in the study of the Khanty language: Khanty, like Hungarian and Finnish, is a Uralic language, and the Hungarians and Finns have always paid great attention to finding out the linguistic relatives of their languages, studying and describing them. In the middle of the 19th century, rich folklore material on the Ural and Berezovsky dialects was collected by Hungarian scholar Antal Reguly. Antal Reguly was the first to prove the relationship between Hungarian, Mansi, and Khanty. In 1858-1859, Finnish explorer Karl August Engelbrekt Ahlqvist visited the Northern Khanty and published texts, a dictionary and a grammar in Helsinki in 1880. In 1898–1899, the materials on the Ural Khanty were collected by the Hungarian researcher József Pápai. The vocabulary data on all three Khanty languages were collected by another remarkable Finnish linguist Kustaa Karjalainen at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries. In 1948, Finnish researcher Yrjö Toivonen edited the dictionary compiled by Kustaa Karjalainen, which was subsequently published in two volumes (1200 pages).

Scholars beyond Hungary and Finland have also contributed to the research of Northern Khanty. For example, Irina Nikolaeva published a description of the Ural (Obdor) Khanty in 1995, and collected the Northern Khanty corpus with audio recordings and transcriptions in Latin alphabet, grammar analysis (in English) and English translation of the texts. Currently, the formalization and research of the Northern Khanty language is performed by scholars from Khanty-Mansiysk (Ob-Ugric Institute of Applied Research and Development), Novosibirsk (Institute of Philology of the RAS), Moscow (Institute of Linguistics o.f the RAS, Moscow State University and the Higher School of Economics), St. Petersburg (Institute of Linguistic Studies of the RAS), as well as from universities in Hungary, Finland, and Germany.